Introduction

The social sciences are currently developing an understanding of the underlying foundations of the emergence and destruction of large social organisms such as states. Progress in this direction usually implies works covering large historical periods and revealing the subtleties of the social mechanics of states. To a greater or lesser extent, many scientific bestsellers of recent decades have been devoted to clarifying the birth and decline of the economic and political activity of states. More recently, another landmark work has been added to their number – a book by Peter Turchin (Turchin, 2024). As is traditionally characteristic of Western scientific bestsellers, Turchin’s monograph is based on the author’s many years of research experience and presents the reader with a lot of unexpected, but strictly verified facts and cognitive schemes. In this sense, we can say that the book in question will take its rightful place among the most significant monographs of social orientation, which justifies the attention that will be paid to it in this article.

In this regard, the aim of the article is to review the fundamental ideas of Turchin’s concept, to refract them in accordance with the pressing problems of modernity and to present them in a structural way for easy use. At the same time, some ideas and provisions of the new concept will be concretized and supplemented with cognitive elements making it completer and more operational. The methodological basis of the study is the theory of elites, and the instrumental one is the theory of the production functions.

Elites and their role in the political system: overview of key ideas

With a certain degree of conventionality, but still it can be argued that the first mature ideas about the mutual role of elites and masses belong to Arnold Toynbee: “In short, the normal pattern of social disintegration is the split of a collapsing society into an unruly rebellious substrate and a less and less influential ruling minority. The process of disintegration does not run smoothly: it moves by leaps and bounds from rebellion to unification and back to rebellion” (Toynbee, 2011, p. 21). Thus, the collapse of the state occurs through the breakdown of society into two increasingly less connected groups – the elites (the ruling minority) and the masses (the unruly majority). Therefore, the political instability issues are in one way or another reduced to the interaction of elites and masses.

The next notable step was taken by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. For instance, in their first bestseller they proposed the theory of inclusive institutions, which raises the question of vertical “permeability” of elites and social channels of penetration of the best representatives of the masses (Acemoglu, Robinson, 2015). If the permeability of elites is eliminated through the establishment of extractive institutions that close the access of the masses to the highest echelons of power, the state finds itself unable to support long–term economic growth and technological progress and, as a rule, moves toward a state of political instability. Similar ideas were expressed by Douglass North and his colleagues (North et al., 2011; North et al., 2012).

In their second bestseller, Acemoglu and Robinson reveal the mechanism of horizontal confrontation between elites and masses, during which a so-called narrow corridor is formed in the power coordinates of the two social groups, within which a political equilibrium in the form of a Shackled Leviathan can be achieved; going outside the notorious narrow corridor is fraught with political tension and instability (Acemoglu, Robinson, 2021). Therefore, Acemoglu and Robinson examined the vertical and horizontal interactions between elites and the masses, marking important milestones along the way.

Earlier, Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov took a closer look at the size and quality of elites in the context of secular cycles of political instability (Turchin, 2020; Turchin, Nefedov, 2009). Two findings were important elements of this study: the principle of elite overproduction, according to which a society periodically experiences an excessive increase in the social group of elites; and the phenomenon of asabia, which refers to the collective solidarity of a group of elites. Thus, the focus of attention was on the group of elites, which can change greatly over time, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

The last and quite logical step in the series of studies of elites was Turchin’s book, discussed below, in which the group of elites split into two subgroups – the power–holding political elite and the counter–elite, which has wealth and influence, but no access to political decisions (Turchin, 2024). Since then, the social mechanics has been supplemented by intragroup interactions in relation to the group of elites. These processes will be analyzed in more detail below.

Looking ahead, we would like to point out that works that complement Turchin’s concept have appeared recently. For instance, the research (Balatsky, 2024) projects the idea of elites and masses onto the world economic system “center – periphery”, constructs econometric models based on the postulates of the Findlay – Wilson function (Findlay, Wilson, 1984) and confirming the theory’s workability; in addition, the author considers the issue concerning the impact of the economic system expansion on the effectiveness of the system of public administration and political elites in terms of the theory of institutional erosion (Balatsky, 2023). The work (Ekimova, 2024) introduces a distinction between national and supranational elites, whose interests are localized or not localized within the country of origin, respectively, and showed that the collapse of statehood almost always occurs during the rule of supranational elites. Taking into account the above additions, we can talk about some logical completeness of Turchin’s theory of elites.

Cliodynamics of power: general structural scheme

Peter Turchin introduced a special new term – cliodynamics, which is understood as a certain interdisciplinary scientific field that deals with the establishment of regularities in the course of historical processes and reveals the mechanism of regular repetition of constructive and destructive stages in the life of states. Although there are many skeptical theses against cliodynamics, its critics cannot offer a satisfactory alternative. In this regard, let us consider the main elements of Turchin’s concept, which reveals the sources and driving forces of political cataclysms in states of different historical periods.

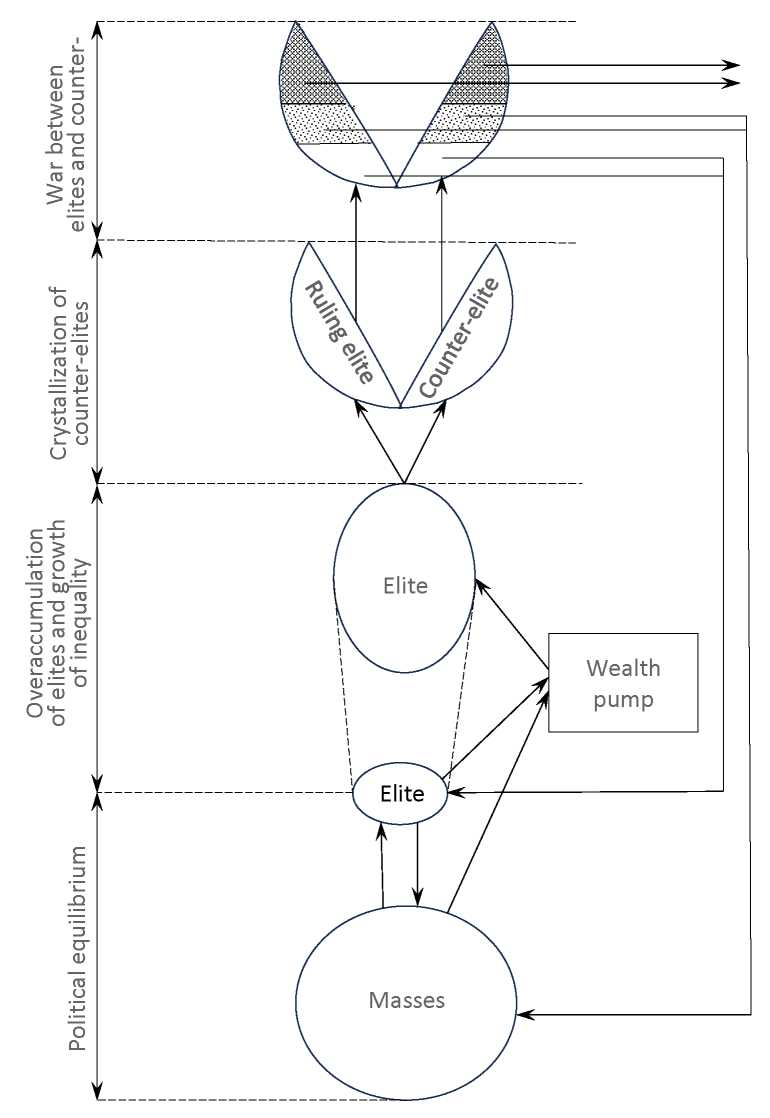

The unfolding of the political cycle stages is based on the interaction of two large social groups – elites and masses (commoners). The elites are a group of powerful individuals involved in making political (state) decisions; the masses include the rest of the country’s population. In a state of political equilibrium, each group is busy with its own business, and only occasionally there is a mutual exchange between them – the most successful representatives of the masses join the ranks of the elites, and the losers from the elites are relegated to the category of commoners (Figure).

Figure. Diagram of the political cycle

The next stage begins with the launching of the so–called wealth pump, which accumulates public revenues and redistributes them in favor of representatives of the masses. The notion of a wealth pump is a convenient metaphor that implies any social mechanism that contributes to the enrichment of new members of society. We should say that this logical move in Turchin’s theory is quite natural and typical for works of economic orientation. Let us mention the black swan theory by N. Taleb, who for its construction also uses the metaphor of the generator of events, which is understood as a spontaneous process of emergence of events with different properties (Taleb, 2009). Both metaphorical concepts are transcendent in nature, for we have no clear idea about them and cannot not only control them, but also seriously influence them. In an earlier tradition, a similar metaphor was introduced by A. Smith in the form of the invisible hand of the market (Smith, 2022). In this sense, N. Taleb and P. Turchin are the continuators of the classical tradition established at the stage of creation of early texts of political economy.

As a rule, the wealth pump “turns on” in periods of some big social shifts, including the formation of new technologies of wide application and sub–sectors. For example, the spread of personal computers and their software led to the emergence of new subsectors, global companies with huge incomes of their managers, etc.

Over time, the wealth pump leads to the phenomenon of overaccumulation of elites, when the initial number of elites increases by multiples of 3–4 times. However, this process faces systemic limitations – the number of persons involved in public decision–making, as a rule, remains relatively stable and cannot increase significantly. In this regard, the growing mass of elites undergoes differentiation up to the split into two hostile subgroups – the ruling elite and the counter–elite, which has wealth and certain influence, but does not directly participate in political decision–making. At this stage of the political cycle, the elites lose the property of asabia, which is understood as the collective solidarity of a social group and the associated ability for joint collective action. The next stage of the political cycle is associated with an outright war between elites and counter–elites, as a result of which the initial number of elites is restored, as well as political stability. At the same time, the war of elites itself leads to the formation of three subgroups among both elites and counter–elites: representatives of elites who retain their position in the political system and representatives of counter–elites who are part of the ruling elite (we show it in white at the top of the figure); elites and counter–elites who lose the political competition and lose their privileges, both managerial and income–generating, and then migrate to the commoners and join the masses (we show it in light shading at the top of the figure); representatives of elites and counter–elites, who are subjected to physical extermination as a result of the unfolding political struggle (at the top of the figure they are shown with darker shading; arrows pointing to the right emphasize their physical elimination from the social system). This completes the political cycle with the restoration of the initial quantitative parameters of elites and masses with subsequent political stabilization.

Paradoxically, the essence of the new theory of elites and political instability is practically exhausted by these passages. Instead of a complex set of cause–and–effect relationships, we are offered the simplest possible analytical scheme of intragroup struggle of elites, which has a universal character and is periodically reproduced in the history of humankind with minor event arrangements.

It is definitely necessary to add obvious fragments of social dynamics to what we have already mentioned. For example, the action of the wealth pump in favor of the enrichment of counter–elites has its downside – the impoverishment of the masses. This circumstance creates fertile ground for radicalization of public sentiments, and counter–elites act as an organizing force that uses the discontent of the masses in its struggle against the ruling elites. However, this is already a standard scheme, which is typical for all political theories.

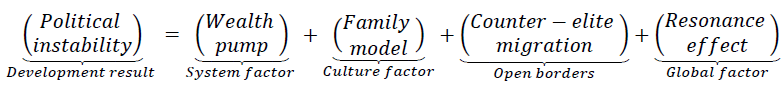

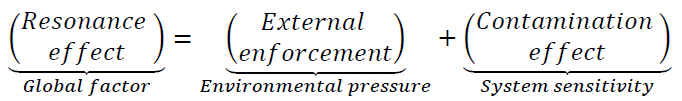

Turchin’s scheme becomes much more interesting when considering the dynamic (cyclical) regularities of political instability periods. Following the author’s logic, historical fluctuations in the phases of disintegration of states can be represented by the following universal structural model:

(1)

(1)

where the resonance effect is in turn represented by two summands:

(2)

(2)

According to Turchin’s theory, the emergence of periods of aggravation of political confrontation, as we have already mentioned, depends to a decisive degree on the transcendental factor in the form of the wealth pump (the first summand in the right part of (1)). However, this factor determines the general flow of events, a kind of historical trend, while the frequency of their occurrence is determined by other groups of reasons. Among them is a specific family model that determines the reproduction rate of the elite class (the second summand in the right part of (1)). In this case, we are talking about the birth of heirs to the representatives of the ruling class. Turchin emphasizes monogamous (European, Christian) and polygamous (Middle Eastern and Asian, Muslim) family models. While in the first type of family only children from one legitimate wife are heirs, in the second type – children from the legally authorized four wives and from all concubines. The direct consequence of this difference in monogamous and polygamous families is the different duration of the political stability cycle: in the former, it is 3–4 times longer than in the latter.

The second determinant of the frequency of the political instability cycles is the migration of counter–elites (the third summand in the right–hand side of (1)). The point is that sometimes the accumulated counter–elites can move to neighboring countries and thus weaken and delay the periods of political conflicts in the states of their origin, where intra–elite contradictions have already accumulated. Conversely, the onset of political cataclysms can be accelerated in countries where foreign elites are “infused” from the outside. In this point, Turchin’s theory is almost completely in line with A. Hirschman’s concept “Exit – Voice – Loyalty”, which shows that it is in line with the classical trends of economic thought (Hirschman, 2009).

The third factor of political instability cycles is the resonance effect (the fourth summand in the right part of (1)). This effect refers to the ability of systems that are close to each other to synchronize their political cycles. This effect is characteristic of both mechanical and social systems and, strictly speaking, has no trivial explanation, thus falling into the category of transcendental phenomena such as the wealth pump, the invisible hand of the market, etc. Nevertheless, the resonance effect has two components that shed light on its nature (equality (2)). For example, global climate fluctuations can accelerate the onset of catastrophic events in countries where the conditions for social revolutions are not yet fully formed, and vice versa, slow down such events in countries where such conditions have long been ripe. Moreover, external “nudges” can occur randomly because they only synchronize cyclical trends in different countries, but do not cause the cycles themselves: accelerating or slowing down the onset of events, they do not act as their source.

The second component of the resonance effect is represented by the contagion effect, which refers to the epidemic spread of infections or certain political sentiments in neighboring countries (the second summand in the righthand side of (2)). For example, outbreaks of plague in European countries in the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries coincided with a general crisis on the continent. The wave of the Arab Spring political epidemic covered Tunisia, Algeria, Jordan, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Iraq, Libya, Kuwait, Djibouti, Western Sahara, Morocco, Burkina Faso, Somalia, Azerbaijan, Lebanon, Palestine and Israel during 2010–2011.

However, all the considered elements of the social mechanics of the birth of political conflicts do not violate the main conclusion: destabilization is generated by the exorbitant growth in the number of the counter–elite and its income, and stabilization of the situation requires the elimination – through physical destruction or social marginalization – of the notorious counter–elite. All other factors are only responsible for the approaching or distant moment of social explosion.

If we summarize the considered scheme, it looks as follows. Structural changes in the system “create” and “turn on” the wealth pump, which acts as a driver of political instability and intra–group struggle; the logic of this process is shown in the figure. When the wealth pump has already sufficiently “pumped up” the political tension in the system, the factors that determine the moment of the start of political conflicts and partly their scale come into play. The logic of these events is reflected in formulas (1) and (2). After the restructuring of the social system and the restoration of political order, the period of prosperity of the state begins until the next cycle of “turning on” the wealth pump.

Passionarity, complexity, evolution: new readings and modern interpretations

Although at first glance, it may seem that the new theory contributes little new to contemporary social knowledge, this is not entirely true. In this regard, it is necessary to focus on four circumstances that produce a new reading of previous ideas about the death of statehood and their political disintegration, as well as about the transformation of states into a new quality.

The first aspect is related to the new sounding of the chaos (complexity) theory. For instance, the elites theory shows that in the process of system development, some of its elements can self–styled hypertrophy and thus violate the initial structure of society with the subsequent loss of its functionality. In other words, some unacceptable deformation of the internal structure of society acts as the initial cause and driving force of all subsequent dynamics of the social system, the direction of which is determined by its desire to restore the disturbed structural equilibrium and its corresponding functional properties. In this case, we are dealing with the self–conditioned development of the social system, which is undoubtedly a great theoretical achievement because it does not “dump” the fundamental effects on external sources and circumstances. The development of society itself sooner or later leads to the emergence of the wealth pump, provoking the disruption of structural equilibrium and conflicts within the system; the chaos that emerged in the course of such transformations can lead to the collapse of the original political integrity (the state), but can also be successfully overcome with the restoration of social order. The “self–cleansing” of the system occurs due to an extremely uncompromising “sequestration” of the hypertrophied social element (elite) that caused the system failure. In this case, the notorious principle of William Ockham’s razor is perfectly fulfilled – no superfluous entities are attracted to explain historical dynamics.

The second aspect is associated with a new reading of the theory of passionarity, which originated in the works of L.N. Gumilev (Gumilev, 2016), and, taking into account the ideas of A. Toynbee regarding the civilizational driver “Challenge – Response” (Toynbee, 2011) and N. Taleb regarding the effect of hypercompensation (Taleb, 2014), has now taken the form of a structural model of evolutionary leap (Balatsky, 2022). However, in addition to all of the above, we now face an important scientific clarification, which is difficult to overestimate: the potential of a nation’s passionarity is concentrated not so much in the masses as in the elites. Simple reasoning allows realizing the obviousness of this fact. First, A. Toynbee’s model “Challenge – Response” is applied mainly to the elites, not to the masses. Second, N. Taleb’s hypercompensation effect in relation to a particular country is realized by the system of public administration, hence, by the power elites. Third, representatives of elites are by definition the passionaries of the nation: “young” or new elitists (in the first generation) come from the masses, who, thanks to their energy and increased vitality, managed to overcome inter–class barriers; the positions of “old” (hereditary) elitists are also subjected to constant tests and their retention requires considerable strength and energy. Thus, passionarity as a certain property of personality is by no means evenly distributed among all members of a large society (state), but is localized mainly in the group of elites. It does not mean that there are no passionaries among commoners, but among them this quality is found orders of magnitude less frequently than among elites. Consequently, the birth of passionarity as a system–wide phenomenon occurs in the circles of elites and from there it spreads to the whole nation with a varying degree of completeness. We should emphasize that the struggle between individual subjects takes place both within the elites and within the masses, but the elites carry the organizational potential that can transform the everyday “squabbling” of individuals into a progressive evolutionary development of the social system.

The third aspect is related to a different perception of the role of the economy and institutions mediated by elites. The point is that the national economy is an extremely dynamic entity capable of self–development and self–sustaining growth, while institutions as formal and informal behavioral norms act as a conservative component of the state. This means that as the economic system becomes larger and more complex, state institutions gradually lose their effectiveness or, in other words, undergo a kind of erosion (Balatsky, 2023). This idea in an overly radical form was expressed by K. Marx. Marx expressed this idea in the form of the law of correspondence of productive forces to production relations (Marx, Engels, 1960). If we proceed from the obvious analogy of production technologies and institutions as some kind of social technologies, we can see the continuity with the idea of “creative destruction” of J. Schumpeter (Schumpeter, 1960). In this case, economic growth fulfills this dual function: on the one hand, it devalues and negates the old institutional system, and on the other hand, it creates demand for completely new institutions. Hence, the paradox of V.M. Polterovich is true: the most important economic growth factor is growth itself (Polterovich, 2002). However, at the stage of negation of old institutions another rule applies: the gravedigger of economic growth is growth itself (Balatsky, 2023). The mismatch between an increasingly complex economic system and outdated institutions is projected into a crisis of governance and a conflict between elites and counter–elites. If this conflict is safely resolved, the new elite builds new institutions (or thoroughly rebuilds the old ones) and organizes social life; otherwise, state integrity may break down, with the subsequent construction of completely new state entities in place of the former ones. Thus, the challenge to the old institutions and elites comes from the continuous evolution of the economic system, and the conductor of systemic discontent is the counter–elites engaged in a power struggle with the entrenched ruling class.

The fourth aspect of the theory of elites is associated with a significant adjustment of the role of inclusive and extractive institutions, the action of which turns out to be non–trivial. For example, according to the Acemoğlu – Robinson theory, elites lose their effectiveness due to the overgrowth of inclusive economic and political institutions into extractive ones with the inherent blocking of vertical social elevators (Acemoğlu, Robinson, 2015). From a formal point of view, this corresponds to a sharp fall in the returns to elites’ activities in the corresponding macroeconomic function (Balatsky, 2024). However, the social mechanics of such a fall in the efficiency of elites turns out to be not fully clarified. In addition, such blockages of vertical diffusion between elites and masses should lead to long–term depression, but not to political upheavals. The latter, according to Turchin’s theory, arise only in the case of penetration of a considerable number of representatives of the masses into the elite environment, which is possible only in the presence of inclusive institutions. At first glance, there appears a logical contradiction in the two theories, but it would be a gross mistake to emphasize their opposition. It is much more correct to consider the mechanism of their complementarity, which can be presented as follows.

Inclusive institutions by no means guarantee political tranquility. On the contrary, they allow the wealth pump to “turn on” at a certain point in time, with subsequent overaccumulation of elites, formation of counter–elites and intragroup struggles. The positive effects of such economic freedom are technological progress, a diverse landscape of Russian companies, and robust economic growth; the price for these benefits is the end of the political cycle with a violent clash between elites and counter–elites. If, instead of inclusive institutions, an extractive regime is established in the country, it means sluggish economic growth and technological progress in the long term, but at the same time, the impossibility of forming political opposition in the form of counter–elites. However, there may be a fork in the road at this point, which becomes more and more likely as time passes. For example, even in conditions of economic stagnation, shadow and openly criminal types of business appear, which contribute to the formation of counter–elites. Suffice it to recall how private fortunes were made in the United States during the Great Depression by bootlegging thanks to Prohibition; later many fortunes were legalized and “spilled over” into other types of business. In the late USSR, extractive economic institutions gave rise to the shadow sector with its semi–criminal elite, while perestroika and economic reforms of 1985 led to the emergence of many businessmen from the shadows and new tycoons. Thus, prolonged over–extractiveness of institutions sooner or later leads to relaxation, the emergence of the wealth pump and the explosive formation of counter–elites. This is the dialectic of inclusive/extractive institutions and counter–elites.

On the one hand, the considered aspects of Turchin’s theory do not contradict the academic traditions of economic science and thus do not break the continuity in the consideration of social processes; on the other hand, they fill some gaps in the traditional knowledge, introducing additional elements and stages of historical dynamics.

Macroeconomic model of counter–elites

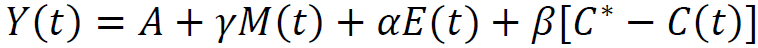

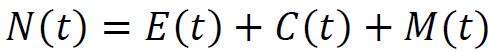

A simple macroeconomic model of elites was proposed relatively recently; it developed Turchin’s ideas within the framework of the production function apparatus (Balatsky, 2024). The analysis of the model showed that an increase in the size of the elite group by itself is unable to have a strong negative impact on the trajectory of economic growth. This implies that the true source of state failure is a decline in the quality of elites rather than a simple increase in their size. However, the above model lacked the subgroup of counter–elites, which in the current version of Turchin’s theory is crucial for historical dynamics. In this regard, for a better understanding of the driving forces of this concept, we will try to take into account this circumstance, for which we will consider a simple macroeconomic model consisting of a simple linear production function and population balance:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

where: Y – GDP output; E – size of ruling elite; C – size of counter–elite; M – masses (commoners); N – population size; А, α, β и γ – linear parameters.

Equation (3) describes the creation of GDP due to the managerial efforts of the ruling elite, the work of the masses and the activities of counter–elites. The specificity is characteristic of the group of counter–elites, which, being few in number, create a competitive environment for the ruling elites and thereby improve the quality of managerial decisions, however, becoming too numerous, the group of counter–elites begins struggling for power uncompromisingly and thereby undermines the entire system of state governance and reduces the effectiveness of the ruling elites. The critical value of counter–elites C* = k*E divides the modes of constructive and destructive influence of counter–elites on the system of governance, where k* is the limit of destructive growth of counter–elites; it defines as the critical share of counter–elites to the number of the ruling elite: at C < C* the presence of counter–elites promotes economic growth, and at C > C* – it restrains it.

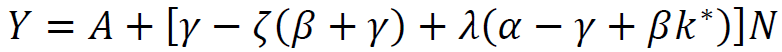

If we introduce structural parameters in the form of the share of elites γ = E/N and counter–elites ζ = C/N in the total population, and assume their invariance over time, the production function (3) can be rewritten in terms of the labor balance (4) as follows:

(5)

(5)

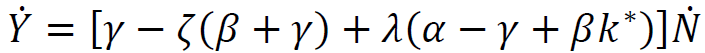

In this case, the joint dynamics of economic and demographic growth will be described by the simplest equation:

(6)

(6)

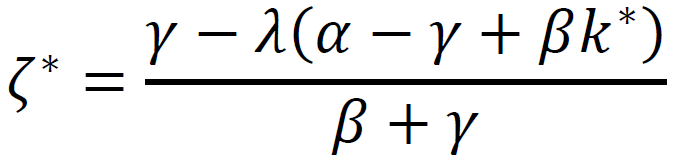

Formula (6) shows that when population growth dN/dt > 0, economic growth dY/dt > 0 takes place if the structural condition ζ < ζ* is satisfied, where ζ* is an upper bound on the share of counter–elites in the total population balance:

(7)

(7)

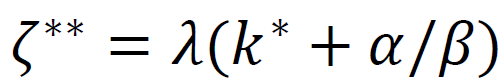

If we take our mind off the influence of the masses, limiting ourselves to the case where elites and counter–elites counterbalance each other’s influence on economic activity, it is easy to derive another bound on the share of counter–elites:

(8)

(8)

We can say that ζ* is the growth admissibility limit of counter–elites of the first kind, and ζ** is the growth admissibility limit of counter–elites of the second kind: ζ** > ζ*. The boundary of the second kind (ζ**) implies a limit to the growth of counter–elites, at which the mutual struggle of the two elite estates does not yet begin to have an overall negative impact on economic growth. If this boundary is crossed, economic growth will continue for some time due to the positive influence of the masses, who, despite the intra–elite struggle, are engaged in creative labor. However, if the boundary of the first kind (ζ*) is exceeded, economic growth becomes impossible and is replaced by a production recession.

Formulas (7) and (8) clearly show that the quantity and quality of elite groups are intertwined in a single process and cannot be considered separately. For example, the growth boundary of the second kind of counter–elites is determined not only by the size of the ruling elite, but also by the ratio in the efficiency of both elite groups (coefficient α/β). The growth boundary of the first kind of counter–elites also depends on the efficiency of the masses. All this allows clarifying the economic meaning of the parameters of the production function (3). For instance, α can be interpreted as the managerial efficiency of the ruling elite, γ as the creative ability of the masses, and β as the coefficient of aggressiveness and influence of the counter–elite. If β is large, even relatively small counter–elites can block the development of the country.

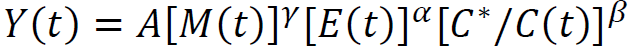

Model (3)–(4) is a variation of the Findlay – Wilson model, which involves groups of managerial class (bureaucracy) and ordinary workers who jointly create the national product (Findlay, Wilson, 1984). However, the Findlay – Wilson model has only two social groups, whereas models (3)–(4) there present three groups; in addition, the former model used a nonlinear Cobb – Douglas production function, while the latter used a linear one. If we follow the tradition of the Findley – Wilson model, function (3) can be rewritten in a nonlinear form:

(9)

(9)

Formal calculations concerning dependence (9) give the same meaningful results as for function (3), therefore we can restrict ourselves to the performed constructions.

Thus, the introduction of the social subgroup of counter–elites into the theory can significantly improve the explanatory power of the simple macroeconomic model of elites. Now the decline in the quality of ruling elites and their managerial efficiency is directly related to the confrontation with counter–elites. This once again proves the fruitfulness of social mechanics that takes into account two antagonistic subgroups of the ruling class.

Empirical confirmation for the theory of elites

Turchin’s theory assumes several theses that can be tested for compliance with real processes. The first thesis in this series is the statement about the overaccumulation of elites in the form of counter–elites and their subsequent physical and social extermination. Thus, the total number of elites should pulsate in time.

As it turns out, this point of the theory is indeed confirmed, and the growth of elites in periods of political instability reaches fourfold. Such inflation of the elite bubble requires an equivalent deflation – to a normal size; and we have original and at the same time quite convincing historical data. For instance, by the time of the apogee of the War of the Roses in England in 1450, the size of elites increased fourfold, after which it also rapidly decreased. Historians have established that the sign of belonging to the elites in Britain at that time was the consumption of wine, while commoners were content with ale. Statistics show that the English elite imported and consumed 20,000 barrels of wine from Gascony each year at its height; by the end of the War of the Roses, less than 5,000 barrels were imported. A similar quadrupling of elites characterized France as the French Age of Discord came to an end; the French population was halved and the number of nobles was halved fourfold between 1300 and 1450 (Turchin, 2024, p. 57). Such examples can be added almost endlessly, but the main point is clear: the overproduction of elites does take place in the history of humankind.

The second empirical challenge is to confirm the operation of the wealth pump. As it turns out, there is no shortage of vivid examples here either. For instance, during the period from 1860 to 1870, which fringed the stage of the American Civil War, the number of American millionaires increased from 41 to 545 people, that is, more than 13 times in just 10 years (Turchin, 2024, p. 162). During the period 1800–1850, the relative number of the country’s millionaires (per 1 million population) increased fourfold. In 1790, the size of the largest fortune in the United States was 1 million U.S. dollars, in 1803, it was 3 million U.S. dollars, in 1830 – 6 million U.S. dollars, in 1848 – 20 million U.S. dollars, in 1868 – 40 million U.S. dollars (Turchin, 2024, pp. 37–38). All this led to the fact that the number of candidates for political office increased from 65 to 242 in the period 1789–1835, and in the Senate and the House of Representatives, it became normal to threaten to kill a political opponent with a knife and a gun, fights with the risk of escalating into a shootout (Turchin, 2024, pp. 39–40); repressions after the American Civil War normalized the disturbed proportions. Something similar happened before 2016, when the overproduction of elites in the U.S. reached its peak and a record 17 candidates for the presidency were nominated from the Republican Party, and the protest of counter–elites brought D. Trump to power (Turchin, 2024, p. 33). The examples of Hun Xiuquan, the leader of the Taiping movement in China, Abraham Lincoln, the winner of the American Civil War, and Donald Trump, the President of the Age of Discord, have an important similarity – the impoverishment of the masses against the background of the overproduction of the elites. In all cases, the wealth pump provided the social parameters necessary for a powerful political conflict and reformatting of the political system.

Checking the efficiency of the family model in equation (1) also gives a positive result. According to theoretical calculations (taking into account the difference in the number of wives and legitimate heirs), the typical duration of political stability cycles in monogamous societies is 200–300 years, while in societies with a polygamous elite, it is 100 years and less. Empirical observations suggest that France and England fit completely within the cycles of monogamous societies. The medieval Islamic historian Muhammad ibn Khaldun showed that in the Maghreb states this cycle is 4 generations or approximately 100 years (Turchin, 2024, p. 69). An additional test of four “cultural areas” of polygamous type – China, Transoceania (the territories of Central Asia around the Amu Darya River), Persia (including Mesopotamia) and Eastern Europe, where Genghis Khan’s descendants, the Genghisids, ruled after his conquest campaigns, shows that in all these areas Mongol dynasties collapsed after about 100 years (Turchin, 2024, p. 70). Thus, the temporal factor concerning political cycles is also confirmed empirically.

The migration factor of counter–elites can be illustrated quite well by the example of the joint history of France and England. The accumulated excess of elites in medieval Britain did not immediately yield negative results. This was facilitated by the outflow of a large part of the English elite to France, which had disintegrated by that time, first in the 1350s and then in 1415. In France, the British elite fought and enriched themselves, but by 1380 the French had consolidated and expelled the invaders from their territory. From that point on, Britain began a period of turmoil – Wat Tyler’s Rebellion, the Glyndwr rebellion, the strengthening of the Lords Appellant and the subsequent overthrow of the House of Plantagenet. When France broke up again in 1415, the British again rushed into its territory, causing serious unrest in England to virtually cease between 1415 and 1448. However, in 1450, the French again managed to defend their country and drive the British back to their island. This event finally “overflowed” the political market of England, which ended with the War of the Roses in 1455–1485, which for the whole world became a model of genocide of surplus elites (Turchin, 2024, pp. 60–63). Thus, the factor regarding elite migration can indeed significantly violate cyclical patterns and shift the starting point of political repressions in time.

The contagion effect has been considered earlier for the case of the Arab Spring, when a political crisis swept through 22 countries in a year and a half with a remarkably similar pattern of implementation. However, recent evidence suggests that the contagion effect in the Arab Spring countries was coupled with a coercion effect. In almost all of these countries, global warming has caused drought, a reduction in the amount of usable agricultural land and the level of agrarian production, falling river levels, erosion of the agrarian revolution, and rural to urban migration. The crowding of the masses into urban slums, their chronic unemployment and appalling living conditions provoked political destabilization in the countries concerned, which took the form of the Arab Spring. The notorious democratic movement was thus a revolt against an ineffective central government that failed to address the problems in time, and the drought became the background noise for political upheaval (Kaplan, 2024). Examples in relation to individual countries confirm what has been said. For example, the uprising of the Syrian population against President Bashar al–Assad was preceded by the destruction of the farmland of 800,000 people in eastern Syria due to drought until 2011 and the death of 85% of their livestock, which provided the impetus for mass migration to Syrian cities with subsequent political unrest. In Yemen, the drought led to a severe drop in the water table, which was “compensated” by the cultivation of qat (a mild water–intensive drug) that agitated the country’s farmers, which was the trigger for the overthrow of Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2012 and the ensuing civil war. Similarly, today’s political migration crisis in the U.S. had the same climatic backstory in the form of a combination of powerful storms, shifts in high precipitation regimes and drought in Central America, which ultimately displaced farmers from their homes and forced them to migrate to a nearby wealthy state. Thus, natural disasters have already become a direct factor in political instability (Kaplan, 2024).

In more distant history, the coercive effect also has its historical embodiments. For example, the English Civil War (1642–1651), the Time of Troubles in Russia (1598–1618), and the collapse of the Ming dynasty in China (1644) occurred around the same time. Conversely, the eighteenth century was a period of domestic tranquility and imperial expansion for all three of these countries. Thus, these two factors also find their historical confirmation.

We can continue the above examples, but the point is clear – Turchin’s theory as a whole has solid empirical support.

Forms of government and typology of ruling classes

In Turchin’s theory, the issue of institutional inertia is extremely important, although standing somewhat apart. The fact is that each country relies on certain groups of elites during the formation of its statehood. This is due to geographical and historical circumstances that bring this or that social stratum to the forefront. Subsequently, this tradition is consolidated due to cultural inertia (Polterovich, 1999), which eventually takes the form of institutional inertia. The latter should be understood as the desire of a social system to reproduce its institutional model, including the model of the ruling class. At present, we can define four types of ruling class and the forms of statehood generated by them – theocracy (power of spiritual leaders), plutocracy (power of the rich), militocracy (power of law enforcers) and bureaucracy (bureaucratic power; Table).

Table. Typology of sources of power and ruling classes

|

Source of power |

Ruling class |

Countries |

|

|

history |

present day |

||

|

Ideology (religion) |

Theocracy |

State of the Church, USSR |

Vatican, Iran, Afghanistan (after 2021) |

|

Economy (wealth) |

Plutocracy |

Republic of Genoa, Republic of Venice, Holland, British Empire |

USA, Russian Federation (before 2000), Ukraine |

|

Force (military) |

Militocracy |

Egypt, Russian Empire |

North Korea, Russian Federation (after 2000) |

|

Art (of management) |

Bureaucracy |

China |

Belarus |

History shows that every state tends to be dominated by one or another ruling class – ideological leaders, magnates, military or administrators. It is this particular ruling class that determines the political “agenda”, makes key managerial decisions and determines the trajectory of the state’s development. This circumstance “paints” the politics of all states in a certain color. A classic example of institutional inertia is Egypt, where the state has been ruled by military clans and maintained a stable militocracy since the time of Saladin in the 12th century. Even after the 1952 revolution, Egypt had a succession of generals in power: Mohamed Naguib, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat, and Hosni Mubarak. However, after Mubarak was overthrown, Mohamed Morsi, a representative of the theocracy (Islamic fundamentalists), came to power and was soon replaced again by another military leader, Abdel Fattah Al–Sisi. The effect of the institutional rut in the ruling class model is of paramount importance.

However, the typology introduced is not a pure theory. The fact is that different forms of government have different degrees of vulnerability in critical periods of the state’s history. It is this circumstance that justifies the introduction of a typology of the ruling class. Let us explain what we have said on the most relevant recent historical examples, covering Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

First of all, let us emphasize that the vulnerability of a form of government depends on its relationship with the wealth pump, which is formed imperceptibly in the depths of the national economy and then begins generating financial imbalances and social tensions. Militocracies, theocracies and bureaucracies, as a rule, restrain the emergence and manifestations of the wealth pump, while plutocracies, on the contrary, create this phenomenon themselves and give it excessive dynamism. In such periods, the group self–interest of the ruling elites is capable of subjugating the national and systemic needs with the most negative consequences. Without taking this factor into account, it is almost impossible to understand the divergence of development trajectories of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus after the collapse of the USSR. Thus, in Belarus, the coming to power of A. Lukashenko, who implemented a hybrid form of government of militocracy and bureaucracy, from the very beginning limited the scale of market reforms, including privatization of factories, and actually prevented the formation of a class of oligarchs, which could later oppose him. In other words, it limited elite sprawl and prevented the emergence of a class of counter–elites represented by national magnates. It is this circumstance that underlies the political stability of Lukashenko’s regime. Even the uprising of 2021 in Belarus was taken under strict control by the military–administrative elite of the country and localized at the very beginning of the conflict. After independence, Ukraine followed the exact opposite path, building a “wild” plutocracy, when a large group of oligarchs, fighting among themselves for the country’s economic resources, grew in society in a relatively short period of time. The polarization of this struggle in the form of groups of oligarchs from the west and east of the country created the basis for the future military conflict in Donbass, and the 2014 revolution was possible due to the lack of consensus in the elites, including the subordinate military circles. In some intermediate position was Russia, where after 1991 almost identical to the Ukrainian plutocracy was built with a massive class of oligarchs who physically destroyed each other in the 1990s, but after V. Putin came to power this process was reversed – oligarchic counter–elites were liquidated either through their migration abroad or through social marginalization (removal from office, prosecution, confiscation of property, etc.). Gradually, the Russian plutocracy was replaced by a symbiosis of militocracy and bureaucracy, which resembled the Belarusian system of power more than the Ukrainian one. In 2014 and then in 2022, the military–administrative elite of Russia defeated the plutocracy, which led to the events in Crimea and Donbass, but the existence and confrontation of elites (militocracy and bureaucracy) and counter–elites (plutocracy) in the country persists to this day.

An important aspect of these examples is the genesis of elites in the three countries. For example, Ukraine, which had no historical experience of building an independent state, quickly slipped into a “modern” form of government in the form of plutocracy, which was in every way approved and supported by the U.S., which from the very beginning paired its plutocracy with the Ukrainian plutocracy through American “proconsuls” (Turchin, 2024, p. 235). Russia is a classic example of a temporary departure from the historical traditions of state governance in favor of plutocracy under the auspices of emissaries from the United States, followed by a return to traditional forms of power with reliance on the power bloc (Kryshtanovskaya, 2006). Belarus in the person of A. Lukashenko simply reproduced the Soviet way of government with necessary market arrangements corresponding to the spirit of the time. It is not difficult to see that the construction of plutocracy for each of the two countries has had deplorable consequences, which once again confirms the danger of departing from the historical traditions of maintaining statehood.

An important addition to the above is the following clarification: plutocracy is by no means a “defective” form of government. The fact is that plutocracy in a hegemonic state, which is still the United States, is quite workable not only at the present stage, but also during the period of its foreign policy expansion, which has lasted more than 200 years. If a country faces the need to defend its political sovereignty, the regime of plutocracy becomes a death trap for the state. This is the historical pattern in general terms.

New theory of passionarity: generalizations and additions

Turchin’s new theory of passionarity is undoubtedly an important milestone in understanding the social mechanics of political conflict. However, there are several important points that should be elaborated on for the sake of final clarity.

First, the true driving force behind political movements and revolutions is not the masses, and especially not the proletarians, but the counter–elites, i.e., the failed candidates for the ruling elite. In other words, the revolutionary potential crystallizes not among the poor and oppressed, but in the community of people who have not fully succeeded, i.e. those who have obtained money, influence and knowledge, but not power, and thus, with all their merits, have been excluded from political decision–making. It is this group of people that generates instability and revolutions, it is this social group that forms the core of the nation’s passionarity. Consequently, paradoxically, political problems arise on the wave of economic success, which generates enrichment of a considerable number of commoners with the subsequent growth of their ambition and power ambitions. The masses in this case play the role of those at whose expense the rise of the representatives of counter–elites takes place. And the irony of fate is that the counter–elites, rising from the masses and at the expense of the masses, use them as “cannon fodder” in subsequent political conflicts. This is the true picture of social dynamics, no matter how unsightly it may seem.

Second, the logic of social interactions is such that any attempts of the ruling elite to establish effective management of the wealth pump are doomed to failure. The fact is that it is the wealth pump that allows new passionaries to climb up the social ladder, while the masses lose out under the new economic conditions. At first glance, the ruling elites can closely monitor the signs of the emergence of the wealth pump and, as they emerge, quickly make decisions that prevent the full–scale establishment of a new mechanism of income redistribution. Theoretically, such a scenario is possible, but in this case, there is a risk and even a guarantee that with the neutralization of the wealth pump many progressive trends in the production, technological and institutional spheres will be suspended. The result of such preventive regulation could be the suspension of technological progress and economic stagnation. In this case, the ruling elites will provoke a slightly delayed, but quite frank impoverishment and discontent of the masses with all the consequences that follow. Thus, the ruling elites have to choose between fighting extremely dangerous counter–elites in the medium term and pacifying the desperate masses in the longer term. Very rarely, but still sometimes history disproves this doomed political choice of the elites (for example, the formation of the welfare society in Europe after the Second World War), but these are those happy cases that form precedents, but cannot claim to be the historical norm.

Third, plutocracy as a form of government has the property of political ambivalence. The latter is understood as the following dichotomy: for a country that is a geopolitical hegemon or is in the mode of economic expansion, the effectiveness of plutocracy can be extremely high; otherwise, plutocracy leads to the collapse of statehood or the loss of political sovereignty (in the previous section this issue was already touched upon). This thesis can be supplemented by another property: for countries that are politically (economically) dependent and seek to gain (restore) political sovereignty, the preferred form of government is militocracy, theocracy, or bureaucracy, depending on cultural specifics. The formulated properties are extremely important, but are not explicitly discussed by Turchin. At the same time, they allow us to understand many events of the 21st century: the global success of the U.S. plutocracy; the collapse of Ukraine’s political independence under the conditions of plutocracy; the victory of North Korea’s militocracy in preserving its political and technological sovereignty; the success of Iran’s hybrid model “theocracy + militocracy” in defending its political and economic interests; the rise of China as a new economic leader of the world on the basis of the symbiotic model “bureaucracy + militocracy”. Any deviation from the formulated two conjugate rules of ambivalence in the modern world is fraught with the political collapse of the state. Here, Turchin’s theory closely correlates with N.A. Ekimova’s conclusions regarding the destructive role of supranational elites whose interests are not localized in the country of origin (Ekimova, 2024). The fact is that plutocracy always contains a considerable number of businesspeople with supranational and even comprador interests in its environment; in the dilemma “national/ global” in critical conditions, their choice is on the second scale.

Fourth, the cognitive frame of “elites/counter–elites” implies a natural generalization in the form of projection to the entire geopolitical system of the world, which has not been implemented at the moment and carries interesting analytical possibilities (the first step in this direction is made in (Balatsky, 2024)). For example, already in the second half of the 20th century, the ruling elite in the form of the USA crystallized in the world. However, throughout the 21st century, one could observe the formation of a counter–elite in the form of China. According to historical empiricism, at the peak of antagonism, the number of counter–elites is 3–4 times the number of elites; the population of China is 4.3 times the population of the United States, i.e. the combined size of elites and counter–elites in the world is about 5 times the population of the United States. There is reason to believe that this is the limit beyond which action must begin to resolve the quantitative imbalance that has arisen. Against this background, the problems of other countries that began to protest against the existing order and joined the struggle for the world’s economic resources have been exposed. These are Russia, Iran, North Korea, India and Saudi Arabia; other countries are next in line. All this corresponds to the basic provisions of Turchin’s theory of elites and requires further development.

These are in general terms the additions that Turchin’s concept of elites needs (Turchin, 2024). A more detailed synthesis of the theory of elites is beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion

This article presents a certain structural rethinking of P. Turchin’s theory of counter–elites (Turchin, 2024). This process is expressed in the graphical scheme of the political cycle, revealing the crystallization of ruling elites and counter–elites, in the structural balances (1) and (2), reflecting the factors concerning the political instability dynamics, in the macroeconomic model (3)–(4), linking the political struggle of elites with economic growth, and in generalizations about the logic of interaction between social groups. These elements set an analytical format that can be fruitfully applied to the analysis of political processes in two directions: both current and future events; both intra–country and interstate clashes. These circumstances determine the value of the performed constructions.

The possible applications of the new theory of passionarity have been outlined above only in the most general form, but their potential is by no means limited to this. We have a reason to believe that further application of the new theory can go both in the direction of clarifying the general disposition of political forces and for assessing the growth rate of emerging conflicts and determining the date of their possible resolution. A private, but extremely interesting application of the theory of elites is the phenomenon of the collapse of the USSR, which can be explained today on the basis of the synthesis of the theory of inclusive institutions of Acemoğlu – Robinson and Turchin’s theory of elites.

REFERENCES

Acemoğlu D., Robinson J. (2015). Pochemu odni strany bogatye, a drugie bednye. Proiskhozhdenie vlasti, protsvetaniya i nishchety [Why Some Countries Are Rich and Others Poor. The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty]. Moscow: AST.

Acemoğlu D., Robinson J. (2021). Uzkii koridor [Narrow Corridor]. Moscow: AST.

Balatsky E.V. (2022). Russia in the epicenter of geopolitical turbulence: The hybrid war of civilizations. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 15(6), 52–78.

Balatsky E.V. (2023). Institutional erosion and economic growth. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 16(3), 81–101.

Balatsky E.V. (2024). Elite economics and political instability. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 17(2), 43–63.

Ekimova N.A. (2024). The role of the elites in the evolutionary process: Conceptual framework and modern interpretations. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 17(2), 64–80.

Findlay R., Wilson J. (1984). The Political Economy of Leviathan. Stockholm: Institute for International Economic Studies (Seminar paper, no. 285).

Gumilev L.N. (2016). Etnogenez i biosfera Zemli [Ethnogenesis and the Earth’s Biosphere]. Moscow: AIRIS–press.

Hirschman A.O. (2009). Vykhod, golos i vernost’. Reaktsiya na upadok firm, organizatsii i gosudarstv [Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States]. Moscow: Novoe izd–vo.

Kaplan R.D. (2024). Enter the age of Malthus: The climate crisis, geopolitical disorder, and the rise of the “Praetorian Regime”. The Newstatesman, 3 February. Available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2024/02/enter–age–malthus

Kryshtanovskaya O.V. (2006). Militocracy and democracy in 21st century Russia. Nauchno–prakticheskii zhurnal Severo–Zapadnoi akademii gosudarstvennoi sluzhby, 2, 24–41 (in Russian).

Marx K., Engels F. (1960). Sochineniya. T. 23 [Collected Works. Volume 23]. Moscow: Gos. izd–vo polit. lit–ry.

North D., Wallis J., Webb S., Weingast B. (2012). V teni nasiliya: uroki dlya obshchestv s ogranichennym dostupom k politicheskoi i ekonomicheskoi deyatel’nosti: doklad k XIII Aprel’skoi mezhdunar.nauch.konf.po problemam razvitiya ekonomiki i obshchestva (g. Moskva, 3–5 aprelya 2012 g.) [In the Shadow of Violence: The Problem of Development for Limited Order Societies]. Moscow: ID VShE.

North D., Wallis J., Weingast B. (2011). Nasilie i sotsial’nye poryadki. Kontseptual’nye ramki dlya interpretatsii pis’mennoi istorii chelovechestva [Violence and Social Orders. A Conceptual Frameworks for Interpreting Recorded Human History]. Moscow: Izd–vo Instituta Gaidara.

Polterovich V.M. (1999). Institutional traps and economic reforms. Ekonomika i matematicheskie metody, 35(2), 3–20 (in Russian).

Polterovich V.M. (2002). Political culture and transformational decline. Commentary on Aryeh Hillman’s article “On the Road to the Promised Land”. Ekonomika i matematicheskie metody, 38(4), 95–103 (in Russian).

Schumpeter J.A. (2008). Teoriya ekonomicheskogo razvitiya. Kapitalizm, sotsializm i demokratiya [Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy]. Moscow: Eksmo.

Smith А. (2022). Issledovanie o prirode i prichinakh bogatstva narodov [An Inquiry into the Naure and Causes of the Wealth of Nations]. Moscow: Eksmo.

Taleb N.N. (2009). Chernyi lebed’. Pod znakom nepredskazuemosti [Black Swan. Under the Sign of Unpredictability]. Moscow: KoLibri.

Taleb N.N. (2014). Antikhrupkost’. Kak izvlech’ vygodu iz khaosa [Antifragility. How to Capitalize on Chaos]. Moscow: KoLibri, Azbuka–Attikus.

Toynbee A.J. (2011). Tsivilizatsiya pered sudom istorii. Mir i Zapad [Civilization on Trial. The World and the West]. Moscow: AST: Astrel’.

Turchin P., Nefedov S. (2009). Secular Cycles. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Turchin P.V. (2020). Istoricheskaya dinamika: Kak voznikayut i rushatsya gosudarstva. Na puti k teoreticheskoi istorii [Historical Dynamics: How States Emerge and Collapse. Toward a Theoretical History]. Moscow: Lenand.

Turchin P.V. (2024). Konets vremen [The End of Time]. Moscow: AST.

Official link to the paper:

Balatsky E.V. Elites and Counter-elites in P. Turchin’s Theory of Passionarity // «Social Area», 2024. Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 1–17.