Introduction

The third decade of the 21st century witnessed the onset of geopolitical events that until recently seemed impossible. This, of course, includes the 2022 proxy war in Ukraine between Russia and the United States; military annexation of Nagorno–Karabakh from Armenia by Azerbaijan in 2023; Venezuela’s claims to most of Guyana; and Taiwan as a bone of contention between the United States and China. All these events are related, on the one hand, by the willingness of their participants to use force if necessary; on the other hand, by a long history of accumulated contradictions. There is reason to believe that the world has many similar situations, which urge us to become interested in them on a system–wide basis.

Even an inexperienced observer in all these cases can see some kind of lingering and viscous strategic game, which at some point accelerates and ends with the victory of one of the parties. In this regard, we have the right to ask logical questions: What do all these events have in common? What is their general mechanism? What does this have in store for the world in the future? What should be the policy of different countries and Russia, in particular, in order to maintain their position in such strategic confrontations?

The aim of the work is to get answers to the questions posed. The research methodology is based on a structural analysis of the world economic system; the methodological basis is cross–country comparison on a number of key indicators. The novelty of our approach consists in the introduction of new management concepts, construction of a sovereignty model as an alternative to that of I. Wallerstein, as well as in explaining the phenomenon of strategic advantages and its cyclical nature based on scale effect and its redistribution across the world economic system at different stages of its development. Of particular importance is the proposed quantitative criterion for identifying the fact that one country has strategic advantages over another.

Major civilizational trend: globalization and scale effect

Recent studies of the history of humankind over 70 thousand years convincingly show that the main evolutionary pattern consists in the expansion (globalization) of world production and its acceleration over time (Sachs, 2022). This pattern is based on the so–called scale effect, according to which the growth of production (scale of activity) leads to an increase in its efficiency. In a broader interpretation, a larger market leads to specialization of labor tasks, an increase in the number of inventors and incentives for inventions, which in turn leads to lower costs. In other words, the larger the production, the higher its efficiency and the faster its further production. Thus, throughout its history, humanity has risen and developed due to the economies of scale. This economic effect is the cornerstone of human population dynamics.

The presence of scale effect naturally led to constant competition for it – different countries sought to expand their territories, because this made them even stronger and more effective. It is not surprising that the era of horsemen, according to Jeffrey Sachs, dating from 3000–1000 BC, was marked by the creation of legendary ancient civilizations in the zone of “happy latitudes” (approximately between the 25th and 45th parallels of the northern latitude), and the classical era that followed (1000 BC – 1500) produced a continuous series of successive empires within the Eurasian continent. Further, in the oceanic age (1500–1800), empires became transcontinental and gained the ability to extend far beyond the physical boundaries of the metropolises (Sachs, 2022). It is reasonable to ask the following question: since all these empires invariably collapsed, then why were they created again with such persistence and regularity?

The answer is that each country has tried to “harness” the scale effect and, thus, become stronger; but theoretically it is impossible to determine the limits of this movement; this becomes clear only in the process of expansion itself, when the benefits of expansion are gradually nullified. But through the use of the scale effect, each empire made amazing progress and new evolutionary achievements; otherwise, humanity would have still been dwelling in caves. That is why no historical setbacks could kill the enthusiasm of subsequent conquerors. For example, the historical failure of Napoleon Bonaparte in the campaign against Russia did not cool Adolf Hitler’s desire to wage a war against the USSR. Having once harnessed the scale effect, neither Napoleon, nor Hitler, nor anyone else could abandon its further exploitation.

However, in the capitalist world, manifestations of scale effect have become extremely diverse and nonlinear. We recall that the capitalist era is characterized by a change in the cycles of capital accumulation with the corresponding leader state and two phases – territorial expansion and internal capitalization (Arrighi, 2006). The issue concerning the alternation of monocentricity and multipolarity regimes within the framework of the capital accumulation cycle has already been considered in detail in the literature (Balatsky, 2022). At the stage of the monocentricity regime, when a leader state operates in the world, an order is established for some time in which economies of scale from the external sphere associated with changes in the borders of many countries move mainly to the internal sphere where they are exploited within production companies and enterprises. Later, the scale effect in the domestic sphere also exhausts itself, after which the world economic system switches to a multipolarity regime with its inherent geopolitical destabilization, external expansion and the change of the former borders of many countries, until a new leader country is finally established and a new order is formed, followed by stabilization. Thus, the cyclical change of monocentricity and multipolarity regimes leads to the scale effect being “pushed out” from the inner sphere into the outer sphere and vice versa. We emphasize that the scale effect itself, due to regime change, always works; the exhaustion of its capabilities in one organizational status (for example, external) requires a transition to another status (internal); and so on indefinitely until the final demise of human civilization or a radical change in the nature of social dynamics.

These arguments allow us to better understand the specifics of the present. The United States, having become a global leader at the beginning of the 20th century, and having strengthened its position after 1945, built a world order for itself and actively exploited the economies of scale in the internal corporate sphere (corporations themselves became transnational and were dispersed around the world). However, having reached the peak of its power and economic efficiency in the 1980s, the USA found itself in a situation of gradually diminishing scale effect in the corporate sphere in the following years. By that time, China harnessed this effect and started gaining unprecedented economic power, which today has become approximately equal to that of the USA. In such a situation, the further inertial course of events will not act in favor of the United States, which forces the American establishment to look for a new format of the world order and a new geopolitical configuration. In fact, this means the transition of the leading country to foreign policy activity with the reformatting of the geopolitical space and possible change in the borders of many countries. In turn, some of the outsider countries, which have strengthened over the past decades, are beginning to make increasingly explicit attempts to seize the initiative and use the window of opportunity that has opened up for them in rebuilding the world based on their strategic advantages.

The phenomenon of strategic advantages: essence and specifics

The above provokes a reasonable question: why did countries that possess strategic advantages not use them before?

Finding an answer requires clarifying some points. Until very recently, economics used terms such as outstripping and catching–up development. Within the framework of modern concepts, outstripping development was considered as an alternative to catching–up development: catching–up development implies integration into the world economic system based on the reconstruction of the basic institutions of leader countries; the outstripping development model is based on the construction of new national institutions that ensure progress even in relation to the most advanced countries (Levin, Sablin, 2021). Thus, outstripping development was typical for the countries at the core of the world economic system, which in many respects were leaders, and catching– up development was observed in the countries located on the periphery and semi–periphery. This division allowed economists to study examples of successes and failures in relation to catching– up countries and draw far–reaching conclusions about the reasonableness and expediency of their policies.

For many years, remarkable examples of success were post–war Japan and Germany, and later – the Asian Tigers: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. In some cases, studies of the success stories of these countries obscure fundamental points and highlight neutral factors, for example, establishment of an information society and successful forms of public–private partnership (Belova, 2019). Quite often the literature contains attempts to attribute the success of Japan, for example, to a unique approach to business and human resources (Liker, 2005). In the context of recent political events, such components of the success of late industrialization countries as the creation of an environment for widespread attraction of foreign investment and active participation in the international division of labor seem almost ludicrous (Petukhov, 2023).

However, today it is quite obvious that such arguments are deeply erroneous, although they are not devoid of a certain reason. The fact is that it would be more appropriate to call the four countries “Asian Gophers” rather than “Asian Tigers”: Hong Kong and Singapore are dwarf city–states (the former has already lost its sovereignty), Taiwan is just an island without political autonomy, and South Korea is a smaller fragment of a former single country. It is completely groundless to extend the experience of these dwarf countries to other “fullfledged” countries. But the main thing is that these countries are not sovereign to any extent. South Korea was originally created as a springboard against North Korea and remains so to this day with American military bases on its territory. Hong Kong has even historically been used as a trading haven in China, but now it has already lost its independence and is absorbed by mainland China. Patronage over Taiwan after World War II passed from Japan to the United States and now the island is America’s strategic base against China; this fact has already produced a fairly tight knot of political confrontation between the two giants. Most likely, in the near future the island will reunite with mainland China and finally lose its independence. As for Singapore, it has always served as a transshipment point in the region, was part of Malaysia and even after gaining independence remained in the orbit of the United Kingdom and the United States, as evidenced by its official language, English. Thus, these countries are friendly toward the USA and the Western bloc, and therefore their success is based on support from the world hegemon, for whom this can be considered a kind of political experiment.

These ideas have already received wide support in the scientific literature. Thus, some researchers emphasize that the main factor in the success of the Asian Tigers was the Cold War, when the strategy of “containing communism” encouraged the United States to promote the construction of “good” capitalism as an alternative to Soviet and Chinese influence (Krasilshchikov, 2020). For the same purpose in 1967 the regional integration Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established; it initially included five countries – Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines and was designed, according to the plans of its creators and the United States, to counter the “Red Scare” in the region (Krasilshchikov, 2003). Other studies emphasize that the success of these countries would not have been possible without free trade agreements, which has traditionally been the prerogative of the United States (Novikov, Likhareva, 2020).

We can add that after World War II Japan and Germany were supported by the United States as potential springboards against the USSR; even the unification of East and West Germany under the patronage of the United States also aimed to strengthen the aforementioned anti–Soviet bridgehead. The same motivation became the basis for the “upgrading” of Eastern European countries after 1991 so that they meet modern economic standards, with their subsequent inclusion in the European Union and in the NATO bloc. Even China’s ascent would most likely not have taken place if the United States had not decided to use it in the confrontation with the USSR. The irony of history is that the USSR collapsed, and China over the past years managed to grow enormously and began to consider the United States as its main competitor and usurper of global resources (Kuznetsov, 2018). However, this does not negate the fact that without American investment and technology, as well as without a most–favored–nation trade regime created for China, after which it gained access to the American domestic market, the current success of the eastern giant would have been impossible.

More recent studies have examined the paradox of the ever–growing discrepancy between the results of catching–up development of countries and their goals (Evstigneeva, Evstigneev, 2012; Evstigneeva, Evstigneev, 2013). A more radical opinion was also expressed, according to which the very content of the “correct” policy changes with transition from one modernization stage to another; therefore, attempts to copy someone else’s success are doomed to failure (Polterovich, Popov, 2006). In the light of recent events indicating that Western civilization is in a deep crisis due to the exhaustion of the potential of economic and political competition mechanisms, an opinion is expressed about the need to radically revise development strategies of catching–up countries (Polterovich, 2023).

The concept of catching–up development is joined by a more recent concept of convergent growth, according to which a successful development strategy of a country involves its integration into the global division of labor and global economic trends. It was this strategy that in the second half of the 20th century produced impressive achievements of the Asian Tigers, Japan, and Germany. Conversely, sovereign countries with “undemocratic” political regimes like North Korea, Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, and now Russia have consistently demonstrated poor performance due to an allegedly incorrectly chosen political regime. However, as the researchers point out, amid the confrontation between these countries and the United States, the mutual and uncontroversial linking of endogenous and exogenous drivers of sustainable growth becomes non–trivial (Taran, Zhironkina, 2021).

As for Iran, we recall that in the early 1950s in response to the nationalization of the British oil company, the country was subjected to a boycott of its petroleum products by the United Kingdom and the United States, after which these two countries orchestrated the process of overthrowing the initiator of nationalization, Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. Since 1979, when the Islamic Revolution took place in Iran, the country has been under sanctions for almost half a century; only the scale and severity of punishment have changed. Nevertheless, Iran is making amazing strides in its missile and nuclear programs, medicine and pharmaceuticals, automotive industry and civil infrastructure. The similar situation is typical for North Korea, especially given its nuclear capability and solid military potential, which its neighbor and a recognized Asian Tiger, South Korea, does not possess. In this regard, a reasonable and partly rhetorical question arises: are Iran and North Korea examples of the true success of economic development in the post–war period, despite all the obstacles from the United States?

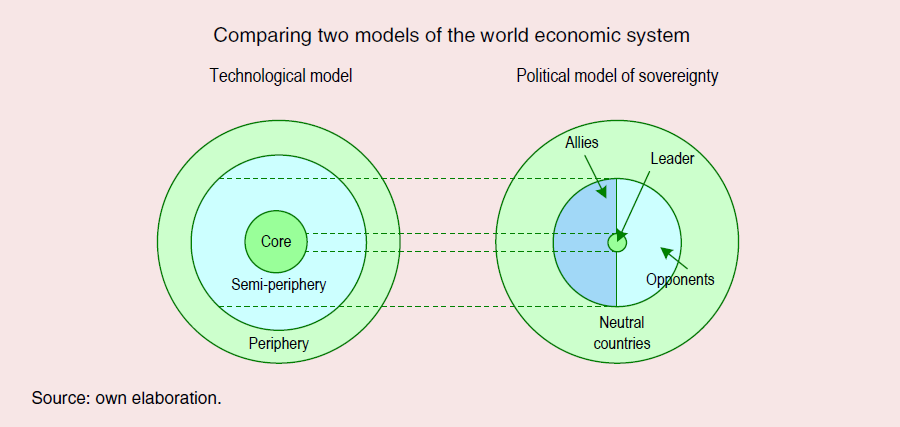

These arguments allow us to question the explanatory capability of the convergent growth concept. Thus, it would be more reasonable to say that in the world today it is necessary to distinguish between independent (natural) and controlled (artificial) development. After Britain gained the status of world hegemon, the successful or unsuccessful development of many countries was associated with direct actions of the leader country, which, in accordance with its strategic priorities, helped some countries, and hindered others. The current US hegemony has become even more extensive and comprehensive than the British one (Arrighi, 2009), which makes the processes of artificial development and containment even more evident. Then independent development takes place only for sovereign nation–states that do not experience noticeable external influence; controlled development is typical for countries with noticeable positive or negative external influence from the leader country. This situation can no longer be adequately explained by the traditional Immanuel Wallerstein model of the world economic system, according to which there are three groups of countries – core, periphery and semi–periphery (Wallerstein, 2006). Under the circumstances, the explanatory relevance of the Wallerstein model loses its universality and the model becomes limited in its applicability for understanding geopolitical processes. Therefore, the technological model requires either an alternative or an addition.

While the Wallerstein model can be called technological, because it divides countries according to the level of technological and economic development, an alternative model can be called political, since it is based on the attitude of countries toward the leader country. Graphically, Wallerstein’s technological model and the political model of sovereignty are shown in the Figure.

In Wallerstein’s model, the core (C) is represented by a relatively small group of the richest and most technologically advanced countries; the semi–periphery (SP) unites a group of developing countries that combine signs of technological successes and failures; the periphery (P) consists of poor and technologically backward countries. In the political model, the core of the world economic system is the leader country (L) (today it is the United States); the second contour is formed by two groups of countries relatively advanced in their technological development – allies (satellites) of the leader (SL) and its opponents (OL); the third contour includes relatively neutral (RN) and, as a rule, underdeveloped countries that have fallen out of the focus of attention of the leader country for one reason or another. Dotted lines in the Figure show that the core of the system in the political model is much smaller than in the technological one, whereas the zone of the second contour, on the contrary, is much wider. Accordingly, the United States encourages the development of its satellites and restrains its opponents, which is directly related to artificial development and artificial deterrence regimes.

Two remarks should be added to what has been said.

First, relatively neutral countries are characterized not only by economic poverty and technological backwardness, but also a lack of natural resources; otherwise they would fall into the category of allies or opponents of the United States. For example, Russia is one of the largest and most diversified suppliers of hydrocarbons, and Iran and Venezuela are unique countries whose hydrocarbon reserves are not depleted, but increase overtime (Balatsky et al., 2016). By a strange coincidence, the political regimes of these countries have long been declared undemocratic by the United States; and the countries themselves are either part of the axis of evil or can be potentially included in it.

The second remark concerns the fact that controlled development in the form of controlled acceleration, strictly speaking, is not an absolute good for the beneficiary country. Actually, this is a kind of political loan, for which the country must pay at some point, although theoretically such a situation may never occur at all. Examples are obvious. South Korea has become a developed country, but in the case of an armed conflict between the United States and North Korea, it will become a bargaining chip in this big game with all the consequences that follow. Ukraine has also been receiving direct and indirect financial support from the United States for a long time; but it paid the price, becoming the territory of a proxy war between the West and Russia. The actions of the United States and the UK to disrupt the supply of Russian hydrocarbons to Europe were primarily aimed at weakening Russia; but as a result, Germany, being an US ally and the industrial leader of Europe, has to pay for this policy, since its economy is becoming uncompetitive in conditions of more expensive raw materials.

It has already been noted that strategic advantages may not manifest themselves up to a certain time. Now it becomes clear why. So, if a country possesses strategic advantages, but within the framework of the established world order cannot adequately use them, because a policy of deterrence by the leader country is being carried out against it, then its potential turns out to be dormant. When the old order collapses and geopolitical turbulence begins, such a country starts “waking up” and “turns on” its advantages in order to use a window of opportunity that has opened and later become an independent factor in transforming the world with a change in its position in a new hierarchy.

Applying the political model of sovereignty instead of the Wallerstein model gives a completely different alignment of forces in the world economic system. For example, the countries of Europe, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, traditionally belonging to the core of the system, in a new interpretation form a group of dependent satellites of the hegemon – the United States; Iran, Russia and North Korea, belonging to the category of semi–periphery, form a group of opponents of the United States. However, both of these subgroups form a single contour of the world economy and are approximately at the same technological and civilizational level. It is interesting that according to Wallerstein’s classification China still belongs to developing countries and falls into the category of semi–periphery, which is very illogical; it also seems problematic to classify it as a core, due to its low per capita GDP. All this once again indicates the low relevance of Wallerstein’s technological model in the new geopolitical context.

Among other things, the above leads to an understanding that the phenomenon of strategic advantages in individual countries is subject to cyclical fluctuations: sometimes it turns out to be artificially “pinned down” by the leading country, sometimes encouraged by it, and in some cases escapes from its control.

Criteria for the phenomenon of strategic advantages

As mentioned, the phenomenon of strategic advantages is of great importance. First, it changes the entire geopolitical landscape of the world every now and again; second, in many cases it initiates the political activity of countries, which can cause an outbreak of all kinds of wars. In this regard, it is legitimate to ask what exactly allows us to talk about the presence or absence of the phenomenon of strategic advantages. Are there quantitative signs of its presence?

A positive answer can be given to the above question. First of all, modern literature examines competitive strategic advantages of companies in the market, as well as various measures of integration of firms to increase their market advantages (Vyakina, 2021). Various schools in understanding the strategic advantages of companies and their typology have already been studied in detail (Gromova, 2019), among which M. Porter’s market positioning strategy has already become a classic (Porter, 2016). More difficult in terms of digitization is the classic concept of understanding the strategic advantages of firms as the ability to coordinate and combine various processes (Teece et al., 1997). In relation to countries, the concept of strategic advantages is usually directly transferred from companies and sometimes supplemented by the concept of strategic interests [1]. However, quantitative criteria are still rarely used in this area, and therefore the following approach can be proposed here.

Previously, a macroeconomic criterion denoting the significance or fundamentality of economic changes was proposed, producing the following classification: differences of less than 10% of the basic (compared) value can be considered insignificant, more than 10 and less than 100% – significant, more than 100% – fundamental (Balatsky, 2018). The last group of differences suggests that multiple changes (more than twofold) of an economic phenomenon indicate its fundamental transformation. The point is that beyond these quantitative differences, we can already talk about a completely different stage of development of the phenomenon in question, which is equivalent to a fundamental (qualitative) change in the phenomenon itself, its rebirth into something else. Summarizing the above, we can formulate the principle of qualitative transformation of an economic phenomenon: when observing multiple differences (changes) in an economic indicator, we can talk about qualitative shifts in the phenomenon (process) under consideration.

The fact that this principle is purely empirical and heuristic has been noted in the literature (Balatsky, 2018). However, this circumstance does not make it less workable. For example, if a person receives an income of x rubles, then they may not even notice an increase of 2.5%; if an income increases by 25%, then this will already be a noticeable improvement in welfare, but the individual’s life will not change radically; if income growth is 250% (i.e. 2.5–fold), then it will be a completely different life (Balatsky, 2018). Another easy–to–grasp interpretation can be taken from the world of boxing. So, an athlete weighing 60 kg is in the light weight category; with an increase in weight by 2% (+ 1.2 kg), a boxer still is in this weight category; with a 20% (+ 12 kg) increase they move to another category and become a middleweight, with a 100% (+ 60 kg) increase they find themselves in the heavyweight division. Representatives of the light and heavyweight divisions cannot compete against each other because of the fundamental incompatibility of their striking power.

This principle works at the micro and macro levels, but at the mega level, when entire countries are compared, it manifests itself in an even more refined form.

Certain methodological observations should be made here. First, the principle of qualitative transformation, as well as any other criteria of this kind, is not universal. For example, it may lose its initial productivity for small/large initial values. In relation to the above example with the welfare of an individual, we can talk about a marginal case when the initial income is so small that even its multiple increase does not lead to a qualitatively different life in comparison with the surrounding world. In the case of boxers, the exact opposite situation is possible, when an increase in average weight even by 50% turns out to be so significant that it leads to a qualitative change in the situation. This limitation should also be taken into account in the case of international comparisons, when marginal objects should be avoided. Second, the quantitative boundary of the qualitative transformation of the system can be discussed, but its very existence is beyond doubt. Theoretically, it can be assumed that the numerical expression of the boundary is different, but the very logic of studying the phenomenon of strategic advantages will remain the same. Since it is impossible to logically deduce this boundary, we can be satisfied with the proposed heuristic assessment.

The above allows us to consider the problem of strategic advantages, which include qualitative advantages of a country in relation to its competitors according to five or six aspects: area, natural resources, scale of economy, population, technological and military achievements. Of course, this list can be significantly expanded and detailed, as for example in program policy documents; however, it is rather inconvenient to operate with several dozen indicators and, most likely, does not make sense to understand the fundamental disposition in the arrangement of countries. We can stick to the following well–verifiable signs of the phenomenon of strategic advantages: 1) area; 2) GDP; 3) population; 4) technological level (per capita GDP / labor productivity); 5) nuclear capability. The natural resources factor is of great importance; however, there are many non–trivial problems concerning its measurement; therefore, we will consciously abandon its use in the future.

When comparing two countries, these features may be further processed using various secondary procedures. For example, private indicators can be averaged, or they can simply add up; there exist more complex algorithms for aggregating individual sides of the country’s potential, but we will refrain from using them.

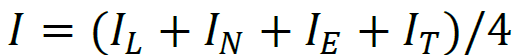

Concretization of the proposed approach involves obtaining a final quantitative assessment of the potential ratio between two countries using the simplest averaging of particular indicators:

(1)

(1)

where IL, IN, IE and IT – indices of the relations of the two countries by area (L), population (N), GDP (E) and gross domestic product (T), respectively; nuclear military potential for the countries under consideration will be taken into account at a qualitative level in the form of a ratio of the fact of presence/absence (+/–) of nuclear weapons due to the fact that quantitative assessment in this case is difficult and, strictly speaking, does not matter much.

Based on previous constructions and reasoning, the criterion of having a strategic advantage in one country compared to another can be expressed as follows:

(2)

(2)

The indicator of per capita GDP, used as a proxy variable of technological progress, deserves some comment. In this case, it is assumed that a completely satisfactory measure of a country’s technological level is labor productivity indicator, which, in turn, is closely correlated with per capita GDP for almost all countries. These circumstances allow us to switch to the indicator under consideration.

Averaging (1) itself is the simplest possible, given the absence of a priori grounds to choose some more sophisticated way of weighing the potentials of different nature. We should note that population density indicator is automatically taken into account in formula (1) due to the indices of land area and population.

Criterion (2) and its heuristic basis have already been discussed above; however, one more argument can be added in the form of F. Lanchester’s square law (Lanchester, 1916). According to this law, in a military clash between two armies, the ratio of their forces obeys the square law, provided that the damage inflicted by one side per unit of time on the other is proportional to the strength of that side. This means that, for example, with a twofold superiority of the forces of one of the parties, its real military advantage will be fourfold (Turchin, 2024, p. 322). Currently, a huge number of articles are devoted to this law (see, for example, Engel, 1954; Ragheb, 2015). This means that in the case of a geopolitical clash between two countries, the preponderance of one of them will soar when its potential increases more than twofold. It is precisely this circumstance that can further justify criterion (2).

Finally, it is quite obvious that the comparison of potentials based on rules (1) and (2) can be carried out not only for selected pairs of countries, but also for different groups of countries, for example, geopolitical alliances and blocs; the logic of calculations remains the same, taking into account the addition of group potentials.

The introduced concept of strategic advantages is of great importance for the global political system, because it produces the presence of asymmetry in the foreign policy of different countries. If a country does not have strategic advantages compared to its neighbor or competitor, then its behavior should be as cautious as possible, and its policy should be extremely verified and peaceful; otherwise, the strategic potential of the competitor will be activated against it with unpredictable consequences. Conversely, a country with strategic advantages and striving to realize its strategic potential should, in certain cases, aggravate the situation and take risks, because only in the case of an aggressive (expansionist) strategy can it fundamentally improve its geopolitical position. Subjective attitudes of the heads of state may block this binary political logic for some time, but a change of leadership is likely to revive it. The discrepancy between objective and subjective factors contributes to the irregularity of the phenomenon of strategic advantages, but does not eliminate it.

The above is of paramount importance for the development of a balanced policy of any country, Russia in particular. This is a non–trivial problem, because an overly aggressive policy of a country with significant strategic potential can lead to dire consequences. Recent history provides us with examples such as France during the Napoleonic Wars and Hitler’s Germany; in more recent times, Iraq gives a corresponding example with its reckless aggression against Kuwait, whose interests were guarded by the United States. As for ancient history, a striking example is Mithridates VI Eupator, who, in an irreconcilable struggle with the Roman Republic, finally lost the Kingdom of Pontus, which was dismembered into pieces and distributed among Rome’s allies. Excessive ambitions of Tigranes II The Great and his alliance with Mithridates also led to the reduction of Great Armenia and its falling under the protectorate of Rome.

In the modern world, the phenomenon of strategic advantages has entered a new phase and is beginning to manifest itself more and more actively in different regions. Let us consider this phenomenon using several of the most telling examples, which will help to clarify the basis of the geopolitical disposition in the world economic system.

The effect of strategic advantages: bilateral relations

Bilateral relations, against the background of the effect of strategic advantages, are mainly typical for neighboring countries. In this regard, let us consider two subgroups of countries from this potential sample – those that ignored this effect with dire consequences for themselves, and those that either gave a decent answer to it or used it for their own purposes. These considerations produce the choice of several pairs of countries, which will be discussed below. We will stipulate in advance that Armenia and Ukraine belong to the first subgroup of countries, while North Korea, Pakistan and Azerbaijan belong to the second. If needed, the number of examples can be increased, but the proposed illustrative material is quite sufficient to understand the essence of the problem under discussion.

1. Azerbaijan / Armenia. The first example is related to the events of 2023, when Azerbaijan annexed the territory of Nagorno–Karabakh by armed means. This story is well known; but already in 1991, when a conflict arose between the two countries over the territory of Karabakh, and Armenia was able to win it back in its favor, it was clear that in the future the situation would be resolved in favor of Azerbaijan.

To map the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, let us consider Table 1, which shows the introduced structural characteristics.

Table 1. Relative indicators of the potential of Armenia and Azerbaijan

|

Relative indicator |

Year |

|

|

1992 |

2022 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

Azerbaijan / Armenia |

2.16 |

3.46 |

|

Economic potential (GDP) (IE) |

||

|

Azerbaijan / Armenia |

5.77 |

3.43 |

|

Technological potential (GDP per capita) (IT) |

||

|

Azerbaijan / Armenia |

2.67 |

0.99 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

Azerbaijan / Armenia |

–/– |

–/– |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

Azerbaijan / Armenia |

2.76 |

|

|

Azerbaijan / (Armenia+Karabakh) |

2.41 |

|

|

(Azerbaijan+Karabakh) / Armenia |

2.91 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

According to Table 1 we see that Armenia entered into the territorial conflict in conditions that can be described as a failure. In all four aspects Azerbaijan surpassed Armenia by more than two times, which corresponds to qualitative superiority. While it is of key importance that over the past 30 years Armenia has not reduced, but deepened its gap in almost all areas. At the same time, in 2022, Azerbaijan’s average advantage in terms of territory, population and economic potential was 3.2, and according to all four indicators I = 2.7, which fully meets criterion (2) and which effectively deprived Armenia of a chance to win in the ongoing territorial dispute. Although the absence of nuclear capability in both countries and approximate parity in technological development leveled the situation a little, it did not radically change it.

The facts denoting Azerbaijan’s comprehensive strategic superiority were visible at the beginning of the conflict, but the Armenian leadership showed extreme short–sightedness in its settlement. It took an irreconcilable and aggressive position on Karabakh (Artsakh), while the situation with the population and the economy was constantly deteriorating. Against this background, Azerbaijan used Türkiye’s support and its own advantage in the availability of natural resources, and the Armenian leadership gradually moved away from Russia, trying to find new allies in the face of the United States and France. This policy resulted not just in the final loss of Nagorno–Karabakh in 2023, it also weakened the country’s condition, and there have been no positive changes in this situation so far. In fact, Armenia has finally lost its political sovereignty and is now a bargaining chip in the game of major geopolitical players, some of whom are too remote to provide prompt assistance (the United States and France). We can assume that a more balanced economic policy, coupled with skillful diplomacy, could have produced better results. However, the main outcome of what has been said is different: one cannot defeat an opponent who is three times stronger, in a direct confrontation; just as one must not provoke such a dangerous neighbor. In similar cases, a much more subtle and balanced policy is needed, excluding direct confrontation and aimed at creating useful bilateral alliances. We emphasize that Table 1 shows that even with the retention of Nagorno–Karabakh, Armenia could not achieve a radical change in the balance of power with Azerbaijan. This suggests a kind of historical mistake by the supreme power of Armenia from the very beginning of the conflict lasting 32 years.

2. Russia / Ukraine. Another vivid example is provided by the relations between Ukraine and Russia, the balance of forces for which is given in Table 2. By the time Ukraine gained its statehood, it was a fairly powerful country. Suffice it to say that it became the largest European state in terms of territory, surpassing the European territory of France; in terms of population it was only 10% inferior to France, which also put it in the first row of European powers. However, having violated military neutrality, Ukraine began a movement toward joining NATO and turn into a country hostile to Russia. It was a rather slippery slope, considering that the potential ratio (1) for the Russia / Ukraine pair in 1992 was I = 8.8, which far exceeded the critical border (2). Despite an overwhelming advantage on the part of its closest neighbor who, in addition, possesses nuclear capability, Ukraine began an extremely risky policy, which in 2014 ended with annexation of Crimea, and in 2022 – incomplete annexation of four more regions – Donetsk, Lugansk, Zaporozhye and Kherson. As a result, in 2022, the potential ratio (1), taking into account the deduction of the five eastern regions for the Russia / Ukraine pair, was already I = 13.9. while the same indicator for the France / Ukraine pair in 1992 and 2022 increased from I = 2.05 to I = 3.98, respectively. Thus, in comparison with Ukraine, the combined power of France, which in 1992 balanced on the border of strategic advantage (I ≈ 2 times), in 2022 reached unconditional superiority (I « 4 times). According to this indicator, Russia has made a leap from 9–fold to 14–fold superiority in 30 years. At the moment, hostilities are underway on the territory of Ukraine and, regardless of the outcome of the military operation, the restoration of its potential is in great doubt.

Table 2. Relative indicators of the potential of Ukraine, Russia and France

|

Relative indicator |

Year |

|

|

1992 |

2022 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

Russia/Ukraine |

2.86 |

4.12 |

|

France / Ukraine |

1.10 |

1.88 |

|

Economic potential (GDP) (IE) |

||

|

Russia / Ukraine |

2.96 |

11.90 |

|

France / Ukraine |

3.25 |

8.40 |

|

Technological potential (GDP per capita) (IT) |

||

|

Russia / Ukraine |

1.03 |

2.89 |

|

France / Ukraine |

2.95 |

4.47 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

Russia / Ukraine |

+/– |

+/– |

|

France / Ukraine |

+/– |

+/– |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

Russia / (Ukraine + eastern regions) |

28.33 |

|

|

(Russia + eastern regions) / Ukraine |

36.77 |

|

|

France / (Ukraine + eastern regions) |

0.91 |

|

|

France / Ukraine |

1.18 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

This shows how Ukraine’s excessively aggressive and risky policy toward its neighbor who has unconditional strategic superiority, has led not to its strengthening, but, on the contrary, to a noticeable weakening. While an example of an alternative strategy is provided by Belarus, which had much more modest indicators compared to Ukraine, but was able to maintain a balanced policy and preserve, and partly strengthen, its geopolitical potential.

3. North Korea / South Korea. A completely opposite example is provided by South Korea and North Korea (Tab. 3). After the division of the country in 1945 and the end of the Korean War (1950–1953), South Korea was developing very dynamically, being in the orbit of the US strategic interests. There is no reliable data to compare the GDP of the two countries, but there are signs that South Korea’s GDP is much higher than that of its northern neighbor. At the same time, North Korea has a slight advantage in terms of territory, and South Korea has lost its strategic advantage in terms of population by now (IN < 2). However, the most important thing is the fact that in 2005 North Korea officially joined the group of countries of the Nuclear Club, while South Korea does not have nuclear capability. Thus, in the 77 years since the division of the Korean Peninsula into two countries, North Korea has been able to reduce the strategic population gap and gain a decisive military advantage, which allows maintaining strategic parity and stable political balance between countries with very different political and institutional systems.

Table 3. Relative indicators of the potential of North Korea and South Korea

|

Relative indicator |

Год |

|

|

1992 |

2022 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

South Korea / North Korea |

2.09 |

1.97 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

South Korea / North Korea |

–/– |

–/+ |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

South Korea / North Korea |

0.83 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

4. India / Pakistan. A couple of neighboring countries, India and Pakistan, provide a similar example to the previous one. These countries used to form a single state, but later complicated political relations arose between them due to territorial disputes. In 2022, the total index of strategic superiority of India / Pakistan was I = 4.85, which shows India’s complete dominance in the tandem under consideration (Tab. 4). Moreover, India joined the Nuclear Club in 1974, and Pakistan did so only 24 years later – in 1998. From that moment on, India’s strategic superiority is restrained, although its advantage in some areas is even increasing. It is a case of unstable equilibrium due to the military factor, although the preponderance of forces clearly remains on the side of India. Nevertheless, Pakistan, with failed initial conditions, was able to level the situation and skillfully maintains an unstable balance.

Table 4. Relative indicators of the potential of India and Pakistan

|

Relative indicator |

Год |

|

|

1992 |

2022 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

India / Pakistan |

7.81 |

6.25 |

|

Economic potential (GDP) (IE) |

||

|

India / Pakistan |

5.24 |

7.81 |

|

Technological potential (GDP per capita) (IT) |

||

|

India / Pakistan |

0.67 |

1.25 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

India / Pakistan |

+/– |

+/+ |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

India / Pakistan |

4.09 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

More such examples can be put forward, but the main thing is clear: the world provides examples when strategic advantages of some countries are successfully and carefully restrained by thoughtful policies of neighboring competitors; there are other examples when irresponsible policy of the leadership of weaker countries leads to their further weakening. Apparently, an avalanche of geopolitical clashes should be expected in the coming years, in which the effect of strategic advantages will play a major role. One of the most telling examples of this kind is Venezuela’s attempt to annex most of the territory of neighboring Guyana. Considering that in 1992 the population of Venezuela was 28.6 times larger than that of Guyana, and in 2022 this advantage was already 34.5 times, it is not surprising that with such a numerical advantage, a major player wants to further strengthen its position at the expense of its neighbor’s rich oil fields. Such expansionist logic will spread throughout the world until a new world order is formed with its usual international checks and balances.

The effect of strategic advantages: prospects and forecasts

The effect of strategic advantages is a living substance. It may suddenly run out, or it may appear almost from scratch. This creates a fair potential for political intrigue in the modern world economic system. Due to this effect, the future becomes almost unpredictable, although its contours can be outlined in advance. Without trying to cover the entire range of possible castings, we will focus only on some of them to illustrate the main theses. We will also focus not on conflict points, but on the centers of future geopolitical activity that will replace the current ones.

For certainty, let us consider Iran, a country that is gaining strength and popularity, and take Germany as its background (Tab. 5). At first glance, the situation is almost hopeless for Iran, but upon closer examination everything turns out to be not so simple. Back in 2010, Iran’s population was 6 million fewer than that of Germany, and in 2022 it was already 5 million more. While in Iran, on average, the population increases by 1 million people every year, in Germany depopulation has begun in recent years. If these trends continue, more than 100 million people will live in Iran by 2035 against 84 million people in Germany; and this is not the limit, considering that Iran’s territory is 4.6 times larger than that of Germany. All sectors of Iran are ready to jump; therefore, a powerful leap in GDP can be expected. At the same time, Iran will certainly join the Nuclear Club in the coming decade, while Germany will not obtain this opportunity due to the patronage of the United States. Besides, Germany, being deprived of cheap Russian energy carriers, is on the verge of uncompetitiveness and is shifting its production to the United States, China and Brazil, while Iran possesses abundant hydrocarbon reserves. Thus, we can argue that the center of European industrial activity is likely to shift toward Iran. In 20–25 years, Iran is likely to become a new global giant, compared to which Germany will be a dwarf.

Table 5. Relative indicators of the potential of Iran and Germany

|

Relative indicator |

Year |

|

|

1992 |

2022 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

Иран / Германия |

0.75 |

1.06 |

|

Economic potential (GDP) (IE) |

||

|

Иран / Германия |

0.30 |

0.30 |

|

Technological potential (GDP per capita) (IT) |

||

|

Иран / Германия |

0.40 |

0.28 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

Иран / Германия |

–/– |

–/– |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

Иран / Германия |

4.61 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

These are small sketches regarding the possible growth of today’s “outsiders” of the global economy. However, the situation is no less impressive concerning today’s leaders. For example, Japan has long been stalled in its development, and everything indicates that this process may take many more years, if not forever. Although the Land of the Rising Sun is actively looking for non–conventional ways to revitalize its economy (Gubaidullina, 2016); it seems to have exhausted the scale effect – there is no longer an opportunity to increase the population on its islands without a drastic deterioration in the quality of life, which is in stark contrast to Iran whose scale effect is just about to be realized (Balatsky, Ekimova, 2023). A situation similar to that of Japan, albeit with its own specifics, is typical for Germany, whose growth limit also seems to have been exhausted.

Of course, there are many such examples. Thus, Türkiye has also overtaken Germany, the most populous country in Europe, in terms of population. We recall that the territory of Türkiye is 2.2 times larger than that of Germany, which indicates its strategic advantage. Given the climatic and other features of these two countries, we can assume that in the future Türkiye may surpass Germany by two times in population, which is about 160–170 million people. Such a result could shift the entire European economy closer to Türkiye, which is followed by another emerging giant, Iran. The latter is almost 1.9 times larger than Pakistan, which has 227 million people; simple calculations show that Iran could accommodate up to 400 million people. Of course, such demographic shifts cannot happen quickly, but already now the advantage of Türkiye and Iran is obvious compared to the leading European countries. Time and a combination of historical events can enhance their initial geopolitical advantages to the level of strategic ones.

There are many counterarguments against such futurological speculations, but they all come across the fact that the phenomenon of strategic advantages is based on objective conditions and on the scale effect. The last three decades have shown an amazing economic, technological and military strengthening due to the economies of scale of China and India, which during this time have overcome poverty and years of stagnation and became giants of world politics. Today, these pioneers, who have already largely squandered the scale effect, are followed by second–generation countries – Iran, Türkiye, Brazil, Algeria, etc. They will shape the economic landscape of the 21st century.

The effect of strategic advantages: lessons for Russia

The existence of the phenomenon of strategic advantages is not new, as well as the existence of a policy of restraining the development of “undemocratic” countries. What does this entail for Russia?

The simple analytical tools used above help to identify Russia’s sore spots and outline strategic directions for its development. Thus, let us consider the data in Table 6. It shows Russia in comparison with the United States, which is not only a leader country, but also a country that actively opposes Russia.

Table 6. Relative indicators of the potential of Russia and the United States

|

Relative indicator |

Year |

|

|

2022 |

2052 |

|

|

Population (IN) |

||

|

USA / Russia |

2.34 |

1.00 |

|

Economic potential (GDP) (IE) |

||

|

USA / Russia |

4.78 |

1.00 |

|

Technological potential (GDP per capita) (IT) |

||

|

USA / Russia |

2.04 |

1.00 |

|

Military potential (nuclear capability) |

||

|

USA / Russia |

+/+ |

+/+ |

|

Territorial potential (IL) |

||

|

USA / Russia |

0.57 |

|

|

Calculated according to: World Bank and IMF. Available at: |

||

The analysis shows that the United States today has absolute strategic advantages over Russia in three of the five aspects. According to them, the average index of US superiority is 3.05, which speaks for itself; in four aspects, except for the military, the criterion of US dominance is also fulfilled: I = 2.43 > 2. Russia’s advantage lies in a larger territory, but it falls short of strategically significant importance; as for military potential, we can assume the presence of some kind of parity. Thus, the first strategic conclusion that follows from Table 6 is that for the next 30 years Russia should not think about its geopolitical hegemony, but monotonously work toward “adjusting” the three failed indices. To do this, one may set targets in 30–35 years, which involve not so much gaining strategic advantages over the United States as simply achieving parity.

Based on what has been said, Russia will have to develop three finely tuned strategies – demographic, economic and technological. All three directions involve extremely ambitious tasks that are unattainable under normal conditions, but in the context of geopolitical turbulence and the breakdown of the old order, the chances become more realistic.

We should note that even after achieving the planned parity between Russia and the United States according to the three aspects, the question of Russia’s possible leadership remains purely metaphorical in many ways. In this regard, even in the long term, one can be satisfied with the country’s worthy place in the global economic system. By that time, new circumstances will arise, in the light of which the question of Russia’s geopolitical primacy can be posed from a different angle, more appropriate to new challenges. A detailed discussion of specific solutions to achieve strategic parity with the United States, and then superiority, is beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion

The issues discussed above allowed us to outline a more comprehensive perspective of the emerging geopolitical shifts.

First, we can argue that the main driver of the upcoming castling of countries will be the scale effect, which sometimes has incomparable reserves in different countries. This effect can be quantified, which makes it possible to map the balance of power in the global political system. In this case, theoretical provisions are successfully combined with computational practice.

Second, using the political model of sovereignty “leader – satellites/opponents – neutral zone” that we put forward indicates the emergence of new hotbeds of geopolitical and economic activity in countries that are opponents of the current hegemon, the United States. Among these are Russia, Iran, Türkiye and other countries with untapped economies of scale. The global onset of multipolarity and geopolitical turbulence is likely to weaken the effect of restraining the economic development of these countries by the United States.

Third, the upcoming parade of sovereignty on the part of large countries, which have been previously restrained by American hegemony for many years, leads to the activation of the phenomenon of strategic advantages, which will be crucial in reformatting the world in the next 10–15 years. This period is likely to be marked by attempts to redefine the borders between many States that find themselves in the zone of the phenomenon of strategic advantages.

Fourth, in the emerging Russia / USA confrontation, the United States is currently the owner of strategic advantages. Russia, which is a fragment of the USSR that collapsed in 1991, has been a classic example of a country with controlled development with a pronounced vector of containment for more than 30 years. At the same time, Russia has its trump cards in the big game and hidden reserves. As for its prospects, the Russian Federation is able to fundamentally strengthen its economic position by launching a long–dormant and still completely unspent scale effect. It is these advantages that the country should realize in the next 30 years. Russia’s “adjustment” of demographic, economic and technological characteristics will take place against the background of the weakening of the former advanced countries and the strengthening of countries that have long remained in the shadows. The formation of effective alliances with these countries will allow Russia to ease the restraining pressure from the current leader, the United States.

We can assume that the practice of designing target indicators for Russia using the method of identifying the phenomenon of strategic advantages will help in working out its development strategy, effectively combining proactive economic growth with a careful and balanced foreign policy position.

References

Arrighi G. (2006). Dolgii dvadtsatyi vek: Den’gi, vlast’ i istoki nashego vremeni [The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times]. Moscow: Territoriya budushchego.

Arrighi G. (2009). Afterword to the second edition of the “Long Twentieth Century”. Prognozis, 1(17), 34–50 (in Russian).

Balatsky E.V. (2018). Russia’s damage from international sanctions: Rethinking the facts. Mir novoi ekonomiki= The World of New Economy, 12(3), 36–45 (in Russian).

Balatsky E.V. (2022). Russia in the epicenter of geopolitical turbulence: Signs of eventual domination. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 15(5), 33–54.

Balatsky E.V., Ekimova N.A. (2023). Identifying regional foci of potential geopolitical activity on the basis of demographic scale effect. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 16(5), 138–154.

Balatsky E.V., Gusev A.B., Yurevich M.A. (2016). Makrootsenka resursnoizavisimosti rossiiskoi ekonomiki [MacroAssessment of the Resource Dependence of the Russian Economy]. Moscow: Pero.

Belova L.G. (2019). Features of innovative development of small advanced countries of the Asia–Pacific region – Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. Rossiya i Aziya=Russia and Asia, 7(2), 31–45 (in Russian).

Engel J.H. (1954). A verification of Lanchester’s law. Journal of the Operations Research Society of America, 2(2), 163–171.

Evstigneeva L.P., Evstigneev R.N. (2012). Dogonyayushchee razvitie: sovremennaya traktovka [Catching–Up Development: A Modern Interpretation]. Moscow: Institut ekonomiki RAN.

Evstigneeva L.P., Evstigneev R.N. (2013). The mystery of catch–up development. Voprosy ekonomiki, 1, 81–96 (in Russian).

Gromova M.A. (2019). Sources of company’s competitive advantages: Outlook of strategy schools. Nauka i tekhnika=Science & Technique, 18(1), 82–88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21122/2227–1031–2019–18–1–82–88 (in Russian).

Gubaidullina F.S. (2016). Transformation of the economic model of Japan. Sovremennaya konkurentsiya, 10(4), 74–89 (in Russian).

Krasilshchikov V.A. (2003). Asian Tigers and Russia: Is bureaucratic capitalism scary? Mir Rossii=Universe of Russia, 4, 3–43 (in Russian).

Krasilshchikov V.A. (2020). Is it possible to repeat the experience of East Asia? The external factors of East Asian ‘miracle’. Kontury global’nykh transformatsii: politika, ekonomika, parvo=Outlines of Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, Law, 13(3), 7–26 (in Russian).

Kuznetsov A.V. (2018). Integration processes in the Asia–Pacific Region with the participation of China and the position of Russia. Finansy: teoriya ipraktika=Finance: Theory and Practice, 22(5), 95–105 (in Russian).

Lanchester F.W. (1916). Aircraft in Warfare; the Dawn of the Fourth Arm. London: Constable and Company.

Levin S.N., Sablin K.S. (2021). Catch–up development vs. forward–looking development: From theoretical models to developmental state practices. Voprosy regulirovaniya ekonomiki=Journal of Economic Regulation, 12(4), 60– 70 (in Russian).

Liker J. (2005). Dao Toyota: 14printsipov menedzhmenta vedushchei kompanii mira [The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer]. Moscow: Al’pina Biznes Buks.

Novikov I.A., Likhareva N.D. (2020). Geographical orientation of exports: Looking beyond the gravity model (on the example of four “Asian Tigers”). Aziatsko–Tikhookeanskii region: ekonomika, politika, parvo=PACIFICRIM: Economics, Politics, Law, 3, 33–50 (in Russian).

Petukhov V.A. (2023). “Asian Tigers”: Experience of economic success. Upravlencheskii uchet=Management Accounting, 11, 126–136 (in Russian).

Polterovich V.M. (2023). Catching–up development under sanctions: The strategy of positive collaboration. Terra Economicus, 21(3), 6–16 (in Russian).

Polterovich V.M., Popov V.V. (2006). Evolutionary theory of economic policy. Part I: The experience of fast development. Voprosy ekonomiki, 7, 4–23 (in Russian).

Porter M. (2016). Konkurentnaya strategiya: metodika analiza otraslei i konkurentov [Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors]. Moscow: Al’pina Pablisher.

Ragheb M. (2015). Lanchester law, shock and awe strategies. Journal of Defense Management, 6(1), 1–3. DOI: 10.4172/2167–0374.1000137

Sachs J. (2022). Epokhi globalizatsii: geografiya, tekhnologii i instituty [The Ages of Globalization: Geography, Technology, and Institutions]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Instituta Gaidara.

Taran E.A., Zhironkina O.V. (2021). Is endogenous growth possible in the Russian economy in the context of economic convergence? Ekonomika i upravlenie innovatsiyami=Economics and Innovation Management, 18(3), 35–46 (in Russian).

Teece D.J., Pisano G., Shuen A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

Turchin P.V. (2024). Konets vremen [End Times]. Moscow: AST.

Vyakina I.V. (2021). Improving methods for assessing economic security at the micro level in the context of digitalization. MIR (Modernizatsiia. Innovatsii. Razvitie)=MIR (Modernization. Innovation. Research), 12(3), 329–342. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18184/2079–4665.2021.12.3.329–342 (in Russian).

Wallerstein I. (2006). Mirosistemnyi analiz: Vvedenie [World–Systems Analysis: An Introduction]. Moscow: Territoriya budushchego.

[1] Russia’s strategic interests in the global economy: A collection of scientific articles (2015). Moscow: Plekhanov Russian University of Economics. 120 p.

Official link to the paper:

Balatsky E.V. The Phenomenon of Strategic Advantages in the 21st Century // «Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast», 2024. V. 17, No. 4. P. 39–57.