Official statistics on labor out–migration processes reflect, on the whole, the situation in the import of foreign labor which, between July 1994 and January 1996, increased 1.9 times. It corresponds to a semiannual growth index of 1.24, as opposed to 1.6 during the previous period. In other words, the absolute number of foreign workers in Russia has been steadily rising, while the relative rate of growth has declined. The semiannual increments of immigrant workers have remained practically unchanged, which points to the linear character of development. Although a quarter of a million people is not a very significant number for the Russian economy, it may be concluded that labor outmigration processes have acquired mature forms. This is also confirmed by the expanded geography of work–force donor countries due to the integration of the Russian and international labor markets (Table 1).

Table 1. Aggregate indicators of labor out-migration

|

Indicators |

January 1, 1994 |

July 1, 1994 |

January 1, 1996 |

|

Number of foreign workers, thousands |

81.6 |

130.5 |

247.1 |

|

Number of Russians leaving the country to work abroad, thousands |

0.9 |

2.3 |

7.4 |

|

Number of foreign work–force donor countries |

45 |

67 |

103 |

During the past two years, the share of the near–abroad countries among the suppliers of labor to Russia has constantly increased (from 43.04 to 55.49%); as a result, in 1996 they were already leading the rest of the world, as a group, by a substantial margin. It is hard to say what exactly was responsible for such a course of events. Yet, in our view, major shifts in any direction can hardly be expected in the near future, given the present global geopolitical structure. This is also true of the structure of the centers of the foreign labor exodus (Table 2). Competition among the three leading regions–Europe, Asia, and the Middle East–will most likely continue, and they will follow closely on one another’s heels. It is quite probable that in the more distant future (after the year 2000), the countries of Africa and Latin America will play a greater role as a huge potential of untapped labor resources. Most of the countries of those continents have not yet taken any steps to enter the Russian labor market, and their geographic remoteness from Russia will hardly permit them to launch a large–scale labor expansion soon.

Table 2. The world’s main regions supplying labor to Russia, %

|

Regions of the world |

January 1, 1996 |

|

Far–abroad countries |

44.51 |

|

including: |

|

|

the Far East and Asia |

15.99 |

|

the Middle East |

13.67 |

|

North America |

0.52 |

|

Africa |

0.06 |

|

Latin America |

0.04 |

|

Australia and Oceania |

0.02 |

|

European countries |

14.21 |

|

including: |

|

|

Eastern Europe |

12.75 |

|

Western Europe |

0.84 |

|

Scandinavia |

0.62 |

|

Near–abroad countries |

55.49 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

For more detailed information on the geopolitical structure of the foreign work force, see Tables 3 and 4. An analysis shows that the concentration of immigrant workers is still high. The “Big Five” (Ukraine, Belarus, Turkey, China, and the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea) account for more than 68% of all foreign workers, and the “Big Ten” (the same countries plus Yugoslavia, Poland, Georgia, Moldova, and Armenia) for about 83%. Ukraine and Belarus supply nearly 72% of all workers from the former Soviet republics, and Turkey, China, the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea, and Yugoslavia supply more than 33% of those workers from the rest of the world. Such geographic concentrations play a positive role, too, in reducing the number of intensive migration zones and thus facilitating labor import control and regulation.

Table 3. The rating of near–abroad donor countries, %

|

Donor countries |

Share in near–abroad labor |

Share in foreign labor |

|

Ukraine |

60.68 |

33.67 |

|

Belarus |

11.12 |

6.17 |

|

Georgia |

4.80 |

2.66 |

|

Moldova |

4.18 |

2.32 |

|

Armenia |

3.88 |

2.16 |

|

Lithuania |

3.77 |

2.09 |

|

Uzbekistan |

3.02 |

1.68 |

|

Estonia |

1.91 |

1.06 |

|

Kazakhstan |

1.64 |

0.91 |

|

Azerbaijan |

1.04 |

0.58 |

|

Tajikistan |

0.89 |

0.49 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

0.44 |

0.25 |

|

Latvia |

0.09 |

0.05 |

|

Turkmenistan |

0.04 |

0.02 |

|

Undivided balance |

2.50 |

1.38 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

55.49 |

Table 4. The rating of far–abroad donor countries, %

|

Donor countries |

Share in far–abroad foreign labor |

Share in foreign labor total |

|

Turkey |

30.15 |

13.58 |

|

China |

20.89 |

9.30 |

|

People’s Democratic Republic of Korea |

12.42 |

5.52 |

|

Yugoslavia |

11.09 |

4.94 |

|

Poland |

5.66 |

2.52 |

|

Slovakia |

3.85 |

1.72 |

|

Bulgaria |

3.78 |

1.68 |

|

Vietnam |

2.04 |

0.91 |

|

Finland |

1.21 |

0.53 |

|

Macedonia |

1.03 |

0.46 |

|

Croatia |

0.99 |

0.44 |

|

Hungary |

0.87 |

0.38 |

|

United States |

0.66 |

0.29 |

|

Germany |

0.50 |

0.22 |

|

Canada |

0.49 |

0.22 |

|

Czech Republic |

0.49 |

0.21 |

|

Rumania |

0.48 |

0.21 |

|

Great Britain |

0.46 |

0.20 |

|

Italy |

0.43 |

0.19 |

|

Mongolia |

0.31 |

0.14 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

0.29 |

0.13 |

|

India |

0.21 |

0.09 |

|

Others |

1.34 |

0.63 |

As predicted [1], the ranking structure of the far- abroad countries has undergone some striking changes. Yet, there were some surprises. Thus, contrary to forecasts, Turkey has left China behind, displaying truly astonishing dynamism. Within two years, it moved from Number 5 to Number 1 in the migration hierarchy, filling practically all areas of Russia with its work force. It may serve as an example of an effective national labor export policy, which Turkey has pursued for many years. Yugoslavia, Poland, and Slovakia have actively joined in the competition, outdistancing Bulgaria, Vietnam, and Germany. The United States and Canada have suddenly stepped up their activity. India has been slowly but surely following up its success. Denmark is practically out of the game.

The foregoing graphically demonstrates the internal tension accompanying the struggle of foreign countries for an economic niche in the Russian labor market. This fact should not be overlooked, though the absolute numbers cited above are by no means impressive and though Russia has, in its traditional style, coped with the problem of labor immigration with relative ease.

The latter conclusion is borne out by, among other things, positive shifts in the sectoral structure of foreign labor employment (Table 5). In the first place, material production is gradually losing ground to nonmanufacturing sectors, thus counterbalancing the one–sided development of foreign employment. There is also a downward trend in the concentration of labor in such giant sectors as construction, industry, agriculture, and lumber. As of January 1, 1994, these sectors accounted for 97.0% of all foreign workers; half a year later, for 92.9%; and, as of January 1, 1996, for 83.9%. The stability of these shifts testifies to their regular and nonaccidental character. Table 5 clearly shows that such market sectors as credit, insurance, technical maintenance, sales, and general business activity are moving into the forefront. In other words, shifts in the sectoral structure of foreign labor conform to the overall trend of change in the Russian economy. It is also evidenced by the larger share of the construction sector, which can give a boost to all of the other industries. Nor can it be disregarded that Russia is gradually assimilating the positive experience of other countries. This applies to the growing power of management and education as major transmission channels for market innovations. The emergence of a sector in the structure of foreign labor during the last year and a half such as information and computer service is a change in the same direction. Considering modem automation and computerization trends, the large–scale employment of experts in computer technologies was a necessary and progressive step in the Russian government’s human resources strategy.

Table 5. Sectoral structure dynamics of foreign labor, %

|

Sectors of the national economy |

January 1, 1994 |

July 1, 1994 |

January 1, 1996 |

|

Material production including: |

98.70 |

98.31 |

95.80 |

|

construction |

30.10 |

38.11 |

54.85 |

|

industry |

26.30 |

31.45 |

19.54 |

|

agriculture and lumber |

40.64 |

23.35 |

9.49 |

|

transportation and communications |

0.67 |

3.16 |

5.81 |

|

trade and catering |

0.99 |

1.31 |

3.62 |

|

geological prospecting |

– |

– |

1.94 |

|

information and computer services |

– |

– |

0.31 |

|

technical maintenance and sales |

– |

– |

0.24 |

|

other areas of material production |

– |

0.93 |

– |

|

Nonmanufacturing sectors including: |

1.30 |

1.69 |

4.20 |

|

business |

– |

0.10 |

2.15 |

|

management |

– |

0.15 |

0.57 |

|

education |

0.11 |

0.37 |

0.54 |

|

housing and utilities |

– |

0.52 |

0.39 |

|

health care and social services |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.23 |

|

crediting and insurance |

– |

0.09 |

0.16 |

|

culture and arts |

– |

0.11 |

0.09 |

|

science and science supporting services |

1.10 |

0.24 |

0.07 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

The infrastructural component of the foreign work force has also increased, and so has the proportion of foreigners in transport and communications. Inasmuch as these sectors have been traditionally underdeveloped, their reinforcement by foreign personnel seems to be perfectly justified.

It merits special attention that, during the period under review (between July 1994 and January 1996), foreign labor appeared in geological prospecting and its influx showed a sharp increase (Table 5). The participation of foreign workers in prospecting points indirectly to the profound interest of the international business community in our country’s natural resources. In view of the shortage of funds for locating resources in Russia and the chronic shortage of investment, this fact can have a far–reaching positive effect on its socioeconomic development.

The occupational and job skill structure of the foreign work force has undergone some slight changes: further development of incipient trends has been registered in three items out of five in share indices in share indices (Table 6). Yet the ranking of occupational and job skill groups has remained practically unchanged, except for the fact that the groups of rare and first–class specialists have changed places. The occupational and job skill structure of 1996 seems to have finally stabilized, and in the future it will only have small fluctuations in the estimates of the share of small occupational and job skill groups. By and large, although the established structure of foreign labor distribution cannot be considered progressive, primarily because of the excessively high proportion of unskilled labor, it appears to be quite natural for the present stage of Russia’s economic development.

Table 6. The occupational and job skill structure of the foreign work force, %

|

Occupational groups |

January 1, 1994 |

July 1, 1994 |

January 1, 1996 |

|

Workers employed for low–skill, nonprestigious, and hard labor |

87.00 |

91.04 |

90.12 |

|

Specialists in rapidly developing and top–priority areas |

4.80 |

3.85 |

3.66 |

|

Rare occupations |

2.40 |

0.80 |

0.41 |

|

Company executives and department managers |

5.30 |

4.29 |

4.89 |

|

First–class specialists and free–lance workers |

0.50 |

0.02 |

0.92 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

As predicted [1], the “liberation” of foreign labor migration from centralized forms of contacts continued. The share of the latter dropped from 52 to 20.9% between 1994 and 1996, while the share of direct contacts rose from 48 to 79.1 %. This fact, as such, testifies merely to a certain maturity of the process while the real problem lies elsewhere. Not subject to international agreements, the management of most of the immigrant labor turns out to be inadequate. The trouble is that there is still no system of normative acts (primarily on the federal level) governing out–migration relations [2, 3]. Although foreign labor problems have not assumed such proportions as to point to a crisis in this area, the adoption of appropriate regulations should not, under any circumstances, be delayed.

The migration waves were most clearly manifested in Russia’s transitional economy in the distribution of immigrant workers according to sex. The initial reconnoitering of the Russian labor market situation by male workers gave way to a massive influx of women immigrants, whereupon the proportion of men again became predominant and reached a natural level of 91.8%.

The information collected in 1996 on labor outmigration, enabled the first systemic evaluation of the diffused structure of foreign labor across Russia. The results of the estimates are presented in Table 7, which clearly shows the three regional giants absorbing the bulk (77%) of immigrant workers – the West–Siberian, Central, and Far–Eastern regions. Another five regions attract 20.2% of foreign workers, while the rest account for a mere 2.5%. In other words, the regional diffusion of foreign labor is obviously uneven. In our view, this is more than just a problem of migration. The influx of foreigners is determined by a set of economic and geographic factors. It means that striking differences in the immigration activity taking place in certain regions are merely an objective reflection of the existing differentiation in their development levels. In all probability, the regional variation of migration will decrease as market processes gain momentum. To reveal the dynamics of regional differentiation in the attraction of foreign labor, either the traditional polarization coefficient [4] or a modified one can be used:

k = Nmin/Nmах (1)

where Nmin is the sum of the shares of several outsider regions and Nmax the sum of the shares of several leading regions. The lower the polarization coefficient, the wider the range of regional variation in attracting foreign labor. The range of k, as a percentage, is from 0 to 100% (strictly speaking, it would be more appropriate, based on formula (1), to refer to the к index as the uniformity coefficient). The estimate for Table 7 shows that the polarization coefficient was only 3.3%.

Table 7. The regional structure of the foreign work force as of January 1, 1996, %

|

Region of Russia |

Share in foreign labor total |

|

West–Siberian |

35.83 |

|

Central |

30.09 |

|

Far–Eastern |

11.38 |

|

East–Siberian |

5.46 |

|

Central–Chernozem |

4.79 |

|

Ural |

3.47 |

|

North–Caucasian |

3.33 |

|

North–Western |

3.15 |

|

Volga |

1.80 |

|

Northern |

0.68 |

|

Volga–Vyatka |

0.02 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

As for the practical aspects of foreign labor import, it can be stated in no uncertain terms that, although really serious problems do not yet exist in this sphere, certain difficulties do arise in practically every region. The main problem is failure to meet registration requirements: delayed registration or extension of permits for work in Russia, the use of unauthorized firms by foreigners, etc. As a result, illegal labor migration is assuming increasing proportions. In 1995, there were 400000 illegal labor immigrants in Moscow alone. The audit, made in Moscow, showed that the Turkish firm Guarantee Koza alone employed 1114 people illegally. There were also delays in the payment of security deposits for the return of foreign workers to their home countries. In Chelyabinsk oblast, nonpayment, a traditional problem of transitional periods, affected foreign workers too: Chinese vegetable growers suffered wage delays. Still more critical situations arose from the chronic insolvency of nearly bankrupt recipient enterprises.

Gradually, the Russian side developed a foreign labor migration mentality favoring immigrants from the far–abroad. The oblast administrations prefer workers from the far abroad to those from the near abroad because the latter are anxious to settle in Russia permanently, while the former consider their stay temporary. Furthermore, chronic underfunding forces many Russian enterprises to downsize their personnel, furlough their workers, and offer part–time work as a substitute. Under these circumstances, many domestic customers prefer to deal with foreign firms (particularly in construction), thus causing tension in the Russian labor market.

The most important institutional change regarding foreign labor migration was the vesting of the Russian Federation’s territories with the ability to regulate the employment of foreign labor (previously, foreign labor migration was regulated on the national level). Now, many major cities, krays, oblasts, and republics adopt their own out-migration normative acts which, in my opinion, is a strategic error on the part of the government (a rational mechanism for the cooperation of federal and local executive bodies is proposed in [5]). The governing bodies of many Russian oblasts share this view.

The new migration problems have stepped up the activity of specialized services and is manifested by the following: systematic migration audits; cancellation of foreign employees’ entry visas; fining firm executives; interdepartmental cooperation among the visa and registration departments of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the border guard services, employment services and centers, trade unions, sanitary and epidemic inspection services, tax inspectorates, and city registration chambers; the introduction of competitive bidding for construction projects, etc.

By way of summing up, it should be stressed that, contrary to the widely held view, foreign labor today is a boon rather than a menace, because its presence contributes to the acceleration of market developments in a sluggish crisis situation. The diversity of factors behind the decision of business entities to employ foreign labor boils down to a triple formula–“better, faster, and cheaper.” Indeed, the work performed by foreigners is characterized by better quality, the shortest possible production time, and relatively low cost as compared to that done by Russians. It prods Russian entrepreneurs and workers to measure up to the standards introduced by the foreign work force.

Let us now examine the present situation in labor emigration. By the beginning of 1996, Russian human resources had spread out into 22 countries of the far abroad, and their number had grown by 3.2 times. The export of Russian workers is developing at a more accelerated tempo as opposed to foreign labor, whose corresponding index is 1.9. It was manifested in the labor import/export correlation, characterized by the following dynamics: 90.7, 57.7, and 33.4%. Yet the number of Russian workers leaving the country is a mere 3% of the number of immigrant workers, which shows that the export of our labor resources is still at an embryotic stage. Although a third wave of labor emigration, characterized by geographic and occupational diversification, is already rising, the wave itself is too weak. No qualitative changes in the process of emigration will occur. It will basically just gain momentum and assume greater proportions in practically all directions, that is to say it will undergo purely quantitative changes.

An analysis of the geopolitical structure of exported Russian labor shows that its concentration per recipient country is still higher than that of imported labor (Table 8). No obvious geographic pattern can as yet be detected in its diffusion. The only aspect that attracts attention is the choice by Russians to migrate to comfortable zones in terms of their natural and climatic conditions. It is also significant that there is now no geographic correlation between donor and recipient countries, that is to say, our workers go precisely to the countries from which practically no labor arrives in Russia. In other words, there is geographic asymmetry in the flows of exported and imported labor, leading to a fairly intricate circulation of labor resources.

Table 8. The geopolitical structure of exported Russian labor as of January 1, 1996, %

|

Recipient countries |

Share in labor emigration |

|

Cyprus |

49.69 |

|

Greece |

17.71 |

|

Bahamas |

6.76 |

|

Malta |

5.13 |

|

Germany |

4.71 |

|

Liberia |

2.92 |

|

Iran |

2.25 |

|

Panama |

1.99 |

|

Japan |

1.74 |

|

People’s Democratic Republic of Korea |

1.74 |

|

Others |

5.36 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

The paucity of available information makes it impossible to make any definite conclusions regarding the age and sex, occupational–job skills, and sectoral structure of Russian labor emigration. As for the basic factors slowing down full–scale development of labor emigration activity, the first stumbling block is a poor knowledge of the recipient country’s language, which automatically cuts off the vast majority of applicants, irrespective of their job skills or personal characteristics. According to regional services, age, health, and other qualifications are less important in the screening of Russian workers.

The second constraint that has a truly disastrous effect on the export of labor is the inadequacy of the country’s infrastructure. According to rough estimates, more than 90% of all Russian emigrants have found jobs with the aid of private employment agencies. The establishment of such agencies, however, has recently slowed (there were only 100 of them at the beginning of 1996 [6]), and many of the existing ones are practically inactive. It seems that business activity to facilitate the employment of Russian citizens abroad should fall within the purview of large firms and not constitute an independent operation. In my opinion, it is effectively performed by tourist firms and large business structures with extensive international contacts. As for the state services handling labor emigration, the picture is a familiar one: the ineptitude of personnel for such work (no knowledge of foreign languages, and an inability to design the appropriate tests and select applicants) and a lack of funds for training.

Fig. 1. Correlation between the number of people departing for work abroad and the size of the Russian diaspora abroad.

The third serious obstacle is of a bureaucratic nature. It includes, among other things, the time–consuming procedures of obtaining exit documents from consulates; in a number of regions, the person seeking employment independently must go to Moscow to have the necessary papers officially endorsed, involving considerable losses of time and money.

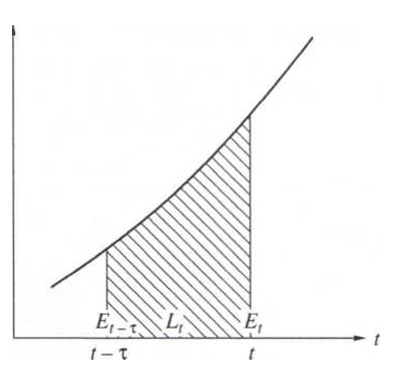

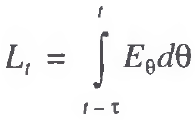

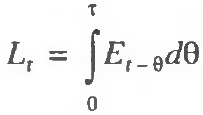

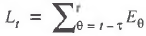

Now let us touch upon a fine point, partly made in [1]. It involves the need to distinguish between the following two indexes in estimating the size of the export of Russian labor: the number of those who departed to work abroad during the survey as compared to the previous period–Et, and the number of Russians workers abroad during the survey–Lt, where t is the period under review. Magnitudes Et and Lt are interconnected by a simple correlation:

(2)

or, in a somewhat modified form,

(3)

where  is the mean term of contracts with the Russian work force [1]. The interrelation of indices Et, and Lt, is shown in Fig. 1, where magnitude Lt is the shaded area.

is the mean term of contracts with the Russian work force [1]. The interrelation of indices Et, and Lt, is shown in Fig. 1, where magnitude Lt is the shaded area.

The differences between the two indices appear to be important primarily because only index Et is subject to direct statistical analysis. To determine Lt, information is required not only on the flow of labor emigrants, but also on the flow of those returning home. Unfortunately, an accurate assessment is practically impossible because accounting data permit only an estimate of the average period of Russians’ work abroad, that is, the mean term of their contracts, followed by an estimate of the size of the Russian diaspora, Lt.

The correlation (2) offers insight into the study of interesting dynamic effects in the formation of emigration waves. For instance, the weak sinusoidal tendencies of index Et may produce, due to resonance effects, a clearly defined oscillating pattern of Lt and vice versa.

The clear distinction between the above two indices seems to be methodologically relevant for estimating the genuine scale of labor emigration as well. If it is assumed that the number of Russian citizens departing for work abroad during 1995 was growing at a uniform rate and the mean term of a contract was at least two years, then the number of Russian emigrant workers as of January 1, 1996, was 20300, or 8.2% of the size of the foreign work force in Russian territory. In other words, the primary data on the state of labor emigration call for additional quantitative processing to clarify the real picture.

Today, all regional bodies point out the unsatisfactory registration of even the initial magnitude Et. Given the administrative problems involved in the collection of correct data on the number of those departing for work abroad, we can hardly expect that it will be possible to make a more objective assessment of the state of affairs in the export of Russian labor in the near future. According to available estimates, the official foreign work force amounts to a mere quarter of its entire strength (about 1 million), whereas, as far as Russian labor emigrants are concerned, this share is still smaller and constitutes not more than 1/10. With due allowance made for the foregoing, the balance of the international exchange of labor resources is somewhat different from that indicated in Table 1. Using the corrections made above, we can easily recalculate the share of Russian emigrant workers in the size of the foreign work force as 20.5%.

It should be stressed that these figures cannot be considered “pure” or final. They are only estimates that can mainly be used in analyzing emerging trends. All point estimates should be treated with caution.

At any rate, this analysis clearly supports the view that labor out–migration has acquired sufficiently mature forms in regard to the import of labor. The development of the export of labor is, on the contrary, lagging far behind and is still at an embryotic stage. Therefore, the state should gradually shift the focus of its attention to the problems of activating the reverse channel of labor out–migration, that is, labor emigration.

References

1. Balatskii, E.V., The Prospects of Labor Out–Migration, Delovoi Mir, December 19–25, 1994.

2. Balatskii, E.V., Working Abroad–Legally or Otherwise?, Sotsial'naya Zashchita, 1996, no. 1.

3. Balatskii, E.V., Migration Is Not Detrimental to Democracy, Inzhenemaya Gazeta, 1996, no. 11 (748).

4. Martynov, D.Ya., Kurs obshchei astrofiziki (A Course in General Astrophysics), Moscow: Nauka, 1988.

5. Balatskii, E.V., International Labor Migration, Vestnik RAN, 1995, no. 2.

6. Entyakov, V. and Zavyalov, S., Working Abroad, Migration, 1996, no. l.

[1] Correlations (2) and (3) have discrete equivalents. Thus, (2) may be written as:

Official link to the article:

Balatskii E.V. Labor Out-Migration Waves in the Transitional Economy// «Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences», Vol. 67. No. 3, 1997. pp. 177–183.